New Jersey Republican state senators continued to push for a moratorium on their state’s ambitious offshore wind energy plans, with an online public hearing May 3 that brought in witnesses from the fishing industry and local activists.

Opponents of offshore wind projects were galvanized by a beach strandings of dead humpback whales from December into March 2023. They questioned if the whales could have been affected by noise from survey vessels working on offshore wind project sites.

Northern New Jersey state Sen. Anthony Bucco said that debate is heard in his Morris County inland district, far from the Jersey Shore: “Everyone is talking about it, and everyone is concerned.”

The prospects for developing ocean wind power once had bipartisan support in New Jersey, but opposition groups emerged in recent years as the speed and scale of offshore wind development grew. Now a split has taken on some partisan aspects, with Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy’s administration fully committed to making wind a key power source, and local Republican legislators opposed.

They are proposing a delay in all work on offshore sites while the whale deaths are investigated. The Republicans’ effort is uphill in the state Legislature, which is firmly controlled by Murphy Democratic allies.

“Nobody can point to with certainty what has caused this,” said state Sen. Vince Polistina.

“What is the harm if we paused this for 30 or 60 days?” said state Sen. Michael Testa.

Homeowners and businesses in tourism-dependent beach communities are a center of resistance.

“We’re finally seeing momentum,” said Paul Kanitra, mayor of Point Pleasant Beach, N.J. “People don’t want their calm and peaceful ocean industrialized.”

Kanitra said his town’s commercial fishing fleet is at risk, and the $15 million a year in seafood value landed at the Fishermen’s Dock Cooperative there.

Offshore wind development “is the single greatest existential threat to commercial fishing in the United States right now,” said Meghan Lapp, fisheries liaison at Seafreeze Ltd. in Point Judith, R.I., a major East Coast center for the squid fishery.

Lapp said “incidental take” permits issued to wind developers by the National Marine Fisheries Service allow builders’ activities to have effects of “harassment” on marine mammals, such as changing their behavior and potentially temporary hearing loss.

But Lapp said her research has found the agency has no data on deafness in baleen whales that hear at low frequencies, including humpback whales that figured in the winter stranding events.

“They do not have any information” on what causes permanent hearing loss in those whales, said Lapp. “Construction is much louder than the surveys,” she added.

New Jersey’s recreational fishing community has a range of opinions on offshore wind development. Some anglers foresee future turbine arrays as new structure with benefits for fisheries such as black sea bass, in the way that the five-turbine Block Island Wind Farm off Rhode Island has become a fishing destination.

But one influential skeptic is Jim Hutchinson Jr., editor of The Fisherman magazine. Studies of electromagnetic field effects around wind turbine power cables in the North Sea have led him to believe they will disrupt fish movements off New Jersey, particularly for summer flounder.

The flounder fishery is a backbone of the state’s party and charter boat fleet, and Hutchinson told the senators he worries the “flounder fishery will be decimated.” If the fishery declines, a fall-off in catches could trigger action by NMFS and management groups to reduce summer flounder quotas, as federal law demands, he added.

NMFS and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management have not taken those concerns seriously, Hutchinson contended.

“I’ve been labeled an anti-green-energy nut,” said Hutchinson. “We’re defamed, demoralized and discarded.” Fishermen’s support for renewable energy has declined as the scale of planned developments grew and “people fully started to believe, ‘This is a lot deeper than I thought,’” he said.

Cynthia Zipf, executive director of the environmental group Clean Ocean Action, was deeply involved in efforts during the 1980s that stopped ocean dumping of sewage sludge and trash off New York and New Jersey. Back then, Zipf said, the New York Bight ecosystem seemed “close to collapse.”

The region’s nearshore waters have revived remarkably in the decades since. But Zipf, unlike some other environmental activists, has long been a skeptic of offshore wind power development as an answer to reducing fossil fuel use.

“When we talk about industrializing the ocean, we have to be very careful,” said Zipf.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have insisted there is no evidence to back up claims that survey vessels were a factor in the winter 2023 whale strandings.

Necropsies on several dead humpback whales showed evidence of ship strikes, according to NOAA. The Marine Mammal Stranding Center at Brigantine, N.J., which responds to those strandings, says it is still awaiting detailed pathology reports on tissue samples. Several dolphin death strandings have shown evidence of pneumonia-like symptoms, possibly linked to parasitic infection, according to the center’s public database.

“However we are seeing a lot of injuries to marine mammals,” said Trisha DeVoe, who works on a whale-watch excursion vessel out of Belmar, N.J. DeVoe said she and other activists ask if the offshore survey noise from sonar and seafloor drill probes could affect the whales’ hearing and make them vulnerable to passing ships.

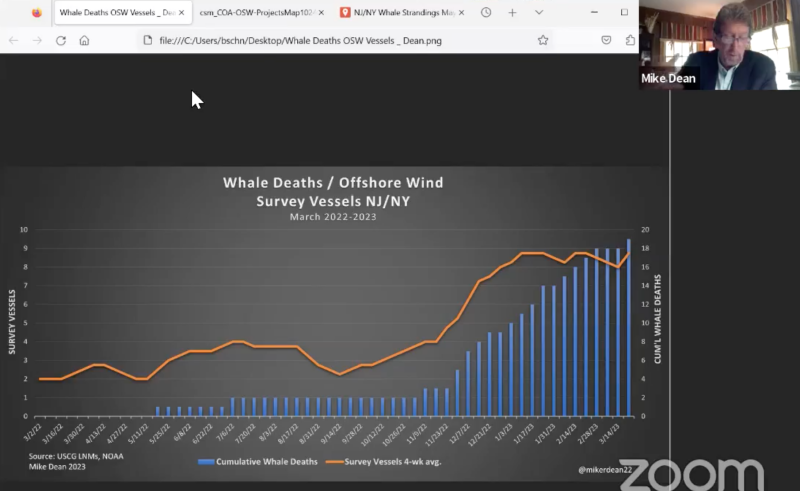

Activist Mike Dean said he referenced Coast Guard Automatic Identification System (AIS) data records to track when survey vessels worked in the New York Bight. Like Zipf, Dean said up to eight vessels were working offshore during the weeks of the whale strandings.

“It just seems plausible,” said Zipf.

.jpg.small.400x400.jpg)