Featured in the June 1987 National Fisherman

Bull Island really isn’t an island at all. In fact, you’d be hard-pressed even to find it on a Virginia map.

Years ago, however, Bull Island was a well-known part of Chesapeake Bay, noted primarily for the abundance of wooden boats built there for Virginia and Maryland watermen.

Actually, a peninsula wedged between the Poquoson River on the north and Back River on the south, Bull Island got its name back when cattle had free reign of the marshes and guts in and around the township of Poquoson. Legend has it that bulls often stood in the middle of the road, stopping horse-and-buggy rigs from passing.

Today, the area is wall-to-wall houses, as the population boom in Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk, and Virginia Beach has engulfed Bull Island. There are few remaining signs of the once thriving, turn-of-the-century boatbuilding trade that gave Bull Island notoriety from one end of Chesapeake Bay to the other.

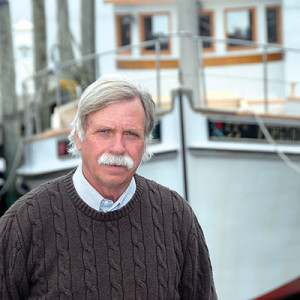

There is one here, though, who still clings to the area’s tradition. William Rollins of Rollins Boat Yard on Bull Island in Poquoson builds time-tested deadrise boats for both work and pleasure. Typical of the old-time shops, Rollins’ yard is off the beaten trail. Located adjacent to Church Street, it’s down a narrow, winding dirt driveway with a line of cedar trees on both sides to mark the way.

Vivacious and friendly, Rollins is the kind of man who knows no big or small job he can’t tackle. This was most evident several years back when he caught the public’s eye by building a traditional Poquoson three-log canoe, the first such workboat completed in the area for over 40 years. But Rollins’ real claim to fame has to be the 23- 28’ deadrise boats that he and his son build for both commercial and recreational buyers.

Since the 1950s, Rollins has turned out over 100 of these hulls, and his boats are used for some of the toughest jobs on Chesapeake Bay. His most popular model is similar in design to the traditional 42-footers used extensively by the region’s crabbers, oystermen, clammers, and fishermen. Rollins’ smaller version has a house/ cuddy configuration like that found on the larger work boats and is among the few deadrise craft of this size and style built on the Chesapeake.

Rollins started back in the 50s, building 16’ and 18’ deadrise skiffs for sport fishermen, duck hunters, and part-time watermen. These boats were powered by outboards and were ideal for the 15- to 25-h.p. kickers popular in those days. However, as outboards grew in size and power, Rollins began building larger hulls to accommodate buyers’ demands.

It was during this period that the 26-and 28-footers came into their own. Since then, rare is the time when there hasn’t been at least one under construction in the yard. Another trend that helped popularize Rollins’ bigger boats was the development of the stern drive engine, which he uses exclusively now. “The outboard simply got outclassed,” he says.

Rollins first started using I/O power plants about 13 years ago when he installed one in a boat, he built for himself. That boat, a 26-footer he named the Starfish, was a great success and has been a source of pride for him ever since. It made Rollins a stern drive fan for life.

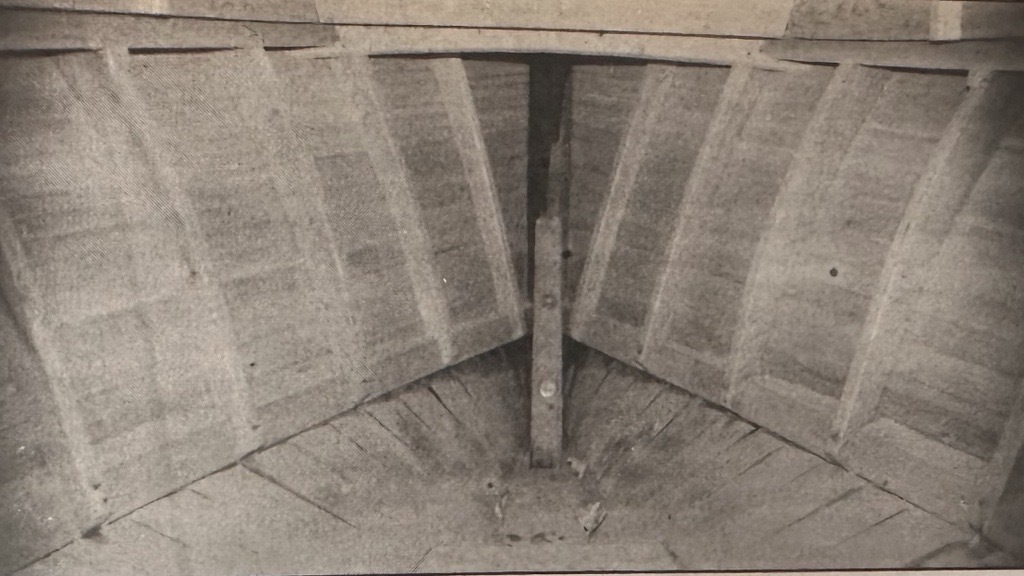

Like most builders on Chesapeake Bay, Rollins doesn’t use plans when he builds. “I’ve had to learn a lot just by doing it again and again until I found the best way,” he says. Over the years, Rollins has made some basic changes in his deadrise hulls. The most noticeable is that he now carries the V in the bow all the way aft.

Most builders of wooden deadrise work boats on the bay flatten the deadrise in the run aft, but Rollins says that practice has been abandoned in his boats. “If she were flat, she’d fishtail on you running tail to a sea,” he says. “We generally have 8” to 12” of V in the bottom. I eyeball it, and if it gets to looking right, I nail it up.”

Still, like most bay builders, Rollins cross-planks the bottoms of all his boats. In those he builds for working watermen, he uses wide fir planks for the bottom, sides, and framing. Workboat keels are also made from fir, with the 26-footer carrying a 6”x 8” timber and the 28 a piece measuring 8” x 10”. “Fir is a tough wood that will stand a hard knock,” says Rollins, “and watermen need that because of the kind of beating a workboat gets.”

Another reason Rollins uses fir for his commercial boats is because it absorbs water readily, which is what he terms “a swelling wood.” Many Chesapeake Bay watermen who order a wooden boat want just that, not one covered in fiberglass. At the same time, they’re looking for a “tight” boat that won’t trouble them with leaks. Because of its swelling properties, explains Rollins, fir fills the bill nicely for such customers. But it’s not, he emphasizes, a good choice is the buyer who does want his boat sheathed in glass. “Any wood that absorbs water shouldn’t be covered in fiberglass because it will come off,” explains Rollins.

But most of Rollins’ sport fishing clients want their boats glassed, and he’s perfectly willing to oblige. In such cases, he switches from fir to juniper planning, covering the hull and decks with three layers of 10-oz. cloth and mat. “I started using fiberglass over wood in the mid-50s when it first came out,” says Rollins. “You can’t use it with fir, but it works great with juniper.”

For years, Rollins bought his juniper from M.R. White of Morgan Corner, N.C. “Mr. White tells me he once went into the Dismal Swamp and pulled up a juniper pole that he knew had been there for 40 years,” says Rollins. “He split it and found the pole was dry inside. That’s why glass stays on juniper so well; it doesn’t absorb water.”

Although Juniper is a soft wood that needs fiberglass covering to protect it from the elements, says Rollins. But he uses juniper strip planking in his sport fishing boats because it enables him to build considerably more flare into their bows.

“I used to build a straight-sided boat,” he says, “but now we flare them. It makes a better-looking boat with more curves in the decking. You also get a drier boat as the water runs away from the hull instead of up over the sides.” Rollins also says the flare provides a little more room on deck and in the cabin.

Another change Rollins has made over the years involves the stem profile of both models. “Back in the 60s, we used to build this boat with a straighter angle on the stem,” he says. “Now we rake the stem so water won’t run up it at ordinary speeds.” Here, too, Rollins relies on fir for its toughness. “The stem will take a beating on a boat no matter whether it’s for a waterman or a hook-and-liners,” he says. “So, we use fir for the stem on all the boats we build.”

The fir frames in Rollins’ boats are spaced 12” to 14” apart and are sawed 6” wide at the top and 3 ¼” at the bottom. He says this provides more strength under the washboards, which need the additional support to withstand the weight of the oystermen who stand on them while working a set of tongs. Both father and son are very particular about getting the maximum strength from each frame. “When we saw one out,” he says, “we always make sure the grain is running with the cut.”

All bolts and nails used as fasteners in the Rollins boats are stainless steel. “Stainless is the best thing they ever came up with for boatbuilding,” says Rollins. “I’m so glad there’s something besides galvanized. If a man’s going to invest 20 years into a boat, he’s a damned fool not to put stainless in her. I don’t even ask if they want galvanized.”

Rollins uses barbed, stainless ring nails, and, on the work boat models, he drills for the countersinks of each fastener. “We tried just driving nails into fir years ago, but you just don’t end up with a good job.” He adds, “It makes for slower work when you have to drill each hole, but that’s not the point; it’s got to be right.” By contrast, the juniper in the sport fishing models is soft enough so that nails drive in smoothly without bending.

All nail holes are capped or filled with “White Star” body putty. Rollins says this filler is particularly good on boats to be sheathed with fiberglass, but he says it also works well on bare wooden hulls. White Star, notes Rollins, has a polyester base, just as does fiberglass comes into contact with the hardened filler, he says the hull is essentially tack-welded to its sheathing. He adds that the body putty also sands down well and is very easy to finish off.

“I’ve put it in places under work boats and it has stayed there for years,” he says. “An oil-based filler doesn’t lock into the wood like a polyester one. Over the years, I’ve tried just about everything. I’ve even mixed sawdust and resin together, but none of it works like a polyester-base filler.”

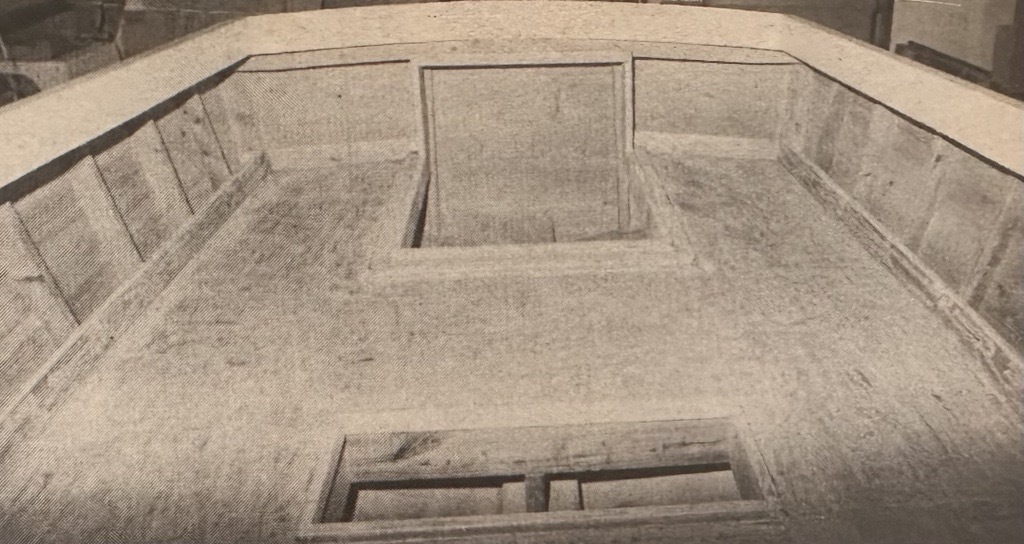

The style of the houses on Rollins’ boats ranges from a simple shelter to a roomy cabin that features a small galley, two bunks, and a head. On most workboat models, he uses the traditional house/ cuddy arrangement found on most larger Chesapeake Bay workboats.

Early on, he reports, some watermen wanted to try the 26- and 28-footer in an open configuration, without a house. “I build several of my larger boats that way,” says Rollins, “and I’ll be damned if they didn’t come back for a cabin! Ain’t nothing like having a little cabin on her when a squall comes up, and you want to get out of the weather.”

Rollins builds either the commercial or sportfishing version of his 26-footer for approximately $1000/ft., not including the engine.