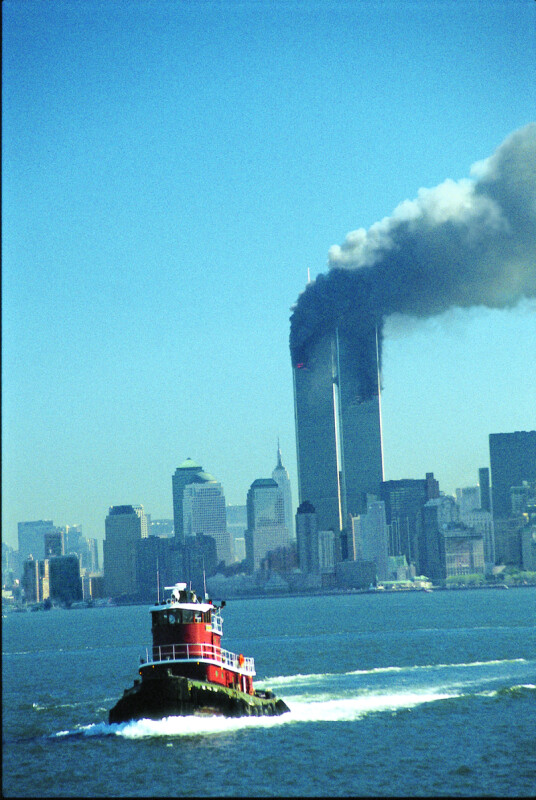

Monday commemorates the 22nd anniversary of the tragic 9/11 terrorist attacks. As we honor the memory of those who perished on that fateful day, we revisit our November 2001 feature, shedding light on the extraordinary efforts of workboats and mariners in the New York region in response to the catastrophe.

Calling all boats

(Original story by Joel Milton)

The heroic efforts of firefighters, police officers, and a host of other rescue workers in the aftermath of the September 11 World Trade Center disaster has been well documented.

But another group of “rescuers” also played an important role that terrible day: commercial mariners. The terrorist attack that left thousands dead also left many of the shocked survivors trapped at the southern tip of Manhattan Island. In their time of need, marine personnel who make their living in and around New York Harbor responded with everything they had. The Coast Guard estimated that about one million people were evacuated from Manhattan by all of the combined marine resources.

Lt. Bob Post was the watch supervisor that morning at the U.S. Coast Guard’s Vessel Traffic Service New York (VTS) control center at Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island. Reports of the first jet crashing into the WTC’s north tower came in almost immediately.

“The phones started ringing off the hook,” Post recalled. “At first, we thought it was just an accident, so we put all the local Coast Guard assets on standby in case they were needed. But after the second plane hit, we knew it was no accident, and we immediately shut down the harbor.”

All ship movements were halted in and around New York Harbor. Small boats from USCG Stations New York, Sandy Hook, and Rockaway were launched, crewed with armed boarding teams. A 1,000-yard-wide security zone was quickly established around Liberty Island (Statue of Liberty). “We put on CNN and saw that the Pentagon had been hit too,” said Post. “We weren’t taking any chances after that.”

QUICK TO MOBILIZE

Shortly after the south tower collapsed, thousands of frightened people fled towards the waterfront to escape the choking dust. About 25 minutes later, the north tower fell.

By then, the evacuation had begun in earnest. The New York Police Department’s Harbor Unit and the Coast Guard immediately put out emergency radio calls for all vessels to come to the vicinity to begin transporting people out of the area. Virtually every kind of small vessel in the port responded. A huge fleet comprised of tugs, ferries, sightseeing vessels, police launches, fireboats, Coast Guard rescue vessels, all seven Corps of Engineers New York District vessels, and a smattering of recreational craft converged on the Battery Park area (located a few blocks south of the World Trade Center at the tip of Manhattan).

“When the buildings came down there was a mad rush of people heading for the water,” said USCG Chief Petty Officer Brandon Brewer, who was on duty that morning at the agency’s Battery Park building. “They were running through the park, hurdling the benches and picnic tables.”

Soon, several dozen tugs had arrived and lined the seawall from one end to the other, side by side. “It was pretty awesome to watch,” said Brewer. “The tug crews built homemade signs and hung up sheets they had spray painted from the railings so people would know what boat was going where. The captains and their crews were on the dock with the police officers and firefighters directing everyone onto the boats. I think it was very calming to people that they would arrive and be told where they needed to go almost right away.

”The visibility was extremely poor, especially on the downwind side. “You could only see about five feet ahead,” said Capt. Gordon Young of the Seastreak Liberty. “We had to come into the dock using the radar. It was really bad.” Seastreak, based in Highlands, N.J., responded with all four of its fast commuter ferries and, by day’s end, had transported about 3,000 people. The evacuees were well-behaved but anxious to leave the area. “If I would have pulled in with a rubber raft, those people would have jumped on it without hesitation,” said Young. “They just wanted to get the hell out of there.”

But Young recalled one man that at first didn’t quite grasp the severity of the situation. He asked where the boat was going and was told Sandy Hook, N.J. “He told me he needed to go to Staten Island. I couldn’t believe it. I told him, ‘Get the f--- on here now; anyplace is better than here!’ Then he jumped right on.

”At one point, a police officer asked Young how many more people the Liberty could carry. “We were at about 200 at that point, so I had room for about 100 more. Then they said to leave a few spots open because there were people who were panicking and jumping into the water at the Battery.”

Fortunately, the Coast Guard and police boats were able to pluck everyone out of the water. The fastest ferries in North America, Fox Navigation’s 45-knot-plus Sassacus and Tatobam, were also in the harbor that morning after bringing commuters to work from Glen Cove on New York’s Long Island. The Sassacus was moored at Liberty Landing Marina in Jersey City, N.J., where Capt. Bob Theofeld was about to leave to attend a ferry safety meeting across the Hudson River in Manhattan. He was standing out on the bow and happened to look up at the World Trade Center just as the first plane slammed into the north tower.

“It hit on the opposite side, so I never saw the plane, just the explosion,” said Theofeld. “I thought that maybe a generator or something else had blown up inside.” He immediately called the office then assembled the crew of the Sassacus to provide assistance. He and the chief engineer then watched as the second jet turned and hit the south tower.

The Tatobam was tied up at Wall the boat underway, and stood off the docks to await further orders. When Tragert left the pier bound for Long Island with his first load of survivors, he saw an image that he said he will never forget. “As we came out of the dust cloud, heading north up the river, I could see all Street’s Pier 11 when the events unfolded. “I don’t recall hearing anything,” said Capt. John Tragert. “I saw a lot of smoke, and then there were these immense clouds of paper falling from the sky. Some of them were burning.”

He immediately got those people walking across the Brooklyn Bridge,” he recalled. “It was completely filled with thousands and thousands of them, most of them coated in dust.” Fox Navigation’s two vessels transported approximately 1,300 evacuees to Glen Cove that day.

According to Pat Smith of NY Waterway, the company’s ferries evacuated over 160,000 people by the end of the day—2,000 of those were medical evacuations to Jersey City where a triage center and ambulances were located. But Smith thinks the number was probably higher. “Nobody was counting for the first hour or two because of the pandemonium.”

Capt. John Mauldin, port captain for Staten Island Ferry, was also ready with a fleet of seven ferries, operated by the New York City Department of Transportation. On a typical weekday, five Staten Island Ferry boats transport approximately 63,000 passengers (104 daily trips) on the 5.2-mile trip between St. George Terminal on Staten Island and Whitehall Terminal in Lower Manhattan. On Sept. 11, it was estimated that Staten Island Ferry transported over 50,000 people, but over a much shorter time span.

The scene at the Whitehall Terminal next to the Battery was reasonably calm at first. “There was a little lull in the crowd and we were able to close the gates and get out of there.” said Capt. John Parese of Staten Island Ferry’s Samuel I. Newhouse.

The 310"x69" ferry’s first evacuation trip was nearly at capacity, about 6,000 passengers. As the Newhouse pulled in to the slip through the thick debris cloud on its second trip in, there were tens of thousands of people waiting, frantic to leave. Some of the people jumped on to the ferry as it pulled away. “It was like a nightmare in that smoke, and you could see the horror on their faces,” said Parese. “There was one guy who I didn’t think was going to make it. He made a spectacular leap from the apron onto the deck, narrowly avoiding a fall into the water. He said he was jumping for his life.”

Brian Walsh, a mate aboard the Newhouse, said the survivors were generally quiet and subdued. “There was no panic or anger. They were mostly sitting in circles, holding hands and praying or crying,” he said.

The passengers also apparently felt the need for as much protection as possible. Without being told, most of them put on lifejackets. “Maybe they just needed to feel that extra little bit of security to help get them through the situation,” Walsh surmised. Walsh and the rest of the crew did as much as they could to keep everyone calm. They also provided first aid to those who needed it. “We kept telling them over and over again that it’s going to be okay, you’re safe.”

As the Newhouse headed across the harbor to Staten Island the thought that the ferry may present a tempting target to terrorists crossed the minds of the crew. “We were worried that we might be (a target) next,” said Parese. “You could hardly miss seeing these big orange boats.” Down in the engine room, chief engineer Gil Ross and his oilers were pushing the four EMD diesel engines as hard as they could. The 7,000-hp ferry has a service speed of 16 knots. “We just wanted to get over there as fast as we could without blowing up the engines and disabling the boat,” said Ross.

Maudlin said that the land-based support personnel should also be recognized for their excellent performance under pressure. “The men on the docks (at Whitehall and St. George terminals) really took the brunt of all this. They somehow kept everyone and everything moving, allowing the boat crews to do what they had to do. It would never have happened without them. At St. George, it was just like an air traffic control center. For over two hours the tugs were coming in nose to tail to drop people off and run back for more.”

A LONG DAY ENDS

At the end of the routes, the ferries and other boats discharged the shaken survivors into the waiting arms of local emergency services personnel, who administered first aid and medical care. People were hosed down and decontaminated if necessary and provided with clean clothing, food, water, and shelter. Transportation arrangements were made for those stranded far from home. “Most of those folks were covered from head to toe with that dust,” said Seastreak’s JoAnne Conroy. “Fortunately, all the injuries were very minor. It seems like you either walked away from it or you didn’t make it at all.”

The largest mass water exodus in the city’s history began to slow down around 4 p.m. and was more or less over by 8 p.m. Staten Island Ferry’s Mauldin vividly recalled the sight of the many firefighters and other emergency personnel who live on Staten Island getting off the ferries at the St. George Terminal that evening. “I will never forget the look on their faces,” he said. “It’s as if you were looking at mannequins. They all had the same shell-shocked expressions and none of them said so much as a word.”

New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani has often referred to the city as “three islands and a peninsula.” It has been a maritime city since the beginning when the Indians were its only occupants. It is safe to say that it would have been impossible to evacuate all the survivors without the combined efforts of the local marine community.

“The Coast Guard and the people of New York were really dependent on the tugs and ferries to make this happen,” said the Coast Guard’s Brewer. “It (the evacuation) looked seamless, like it was perfectly planned, even though you knew that everyone was just winging it.”

Lt. Post of USCG VTS New York agreed. “It was pretty amazing how well everyone came together. Normally these people are all fierce competitors, but they just dropped everything and did a great job.

New York Fast Ferry President John Kaenig offered this observation: “It turns out that all these ferries were invaluable. It’s a shame that it takes something like this for the city to see just how important they are to the transportation infrastructure.” The company’s two ferries, the Bravest and the Finest are named after slang terms for New York City firefighters and police officers. The two boats carried almost 2,300 people to safety on Sept. 11.

“This place has a reputation you know,” said Mauldin. “We may be a little rough around the edges and may not have the polish of some of the other harbors around the country. But when you look at the sheer professionalism that flows around this harbor, from the wheelhouses to the decks to the engine rooms of all these boats and on the docks, it’s truly monumental. The people that work around here are great. Their response to this tragedy proves it.”

This story was originally published in the November 2001 issue of WorkBoat.