Tiny cod fish are reappearing around Kodiak.

Researchers aim to find out if it is a blip, or a sign that the stock is recovering after warming waters caused the stocks to crash.

Alaska’s seafood industry was shocked last fall when the annual surveys showed cod stocks in the Gulf of Alaska had plummeted by 80 percent to the lowest levels ever seen. Prior surveys indicated large year classes of cod starting in 2012 were expected to produce good fishing for six or more years. But a so-called warm blob of water depleted food supplies and wiped out that recruitment.

“That warm water was sitting in the gulf for three years starting in 2014 and it was different than other years in that it went really deep and it also lasted throughout the winter. You can deplete the food source pretty rapidly when the entire ecosystem is ramped up in those warm temperatures,” explained Steven Barbeaux with the Alaska Fisheries Science Center in Seattle.

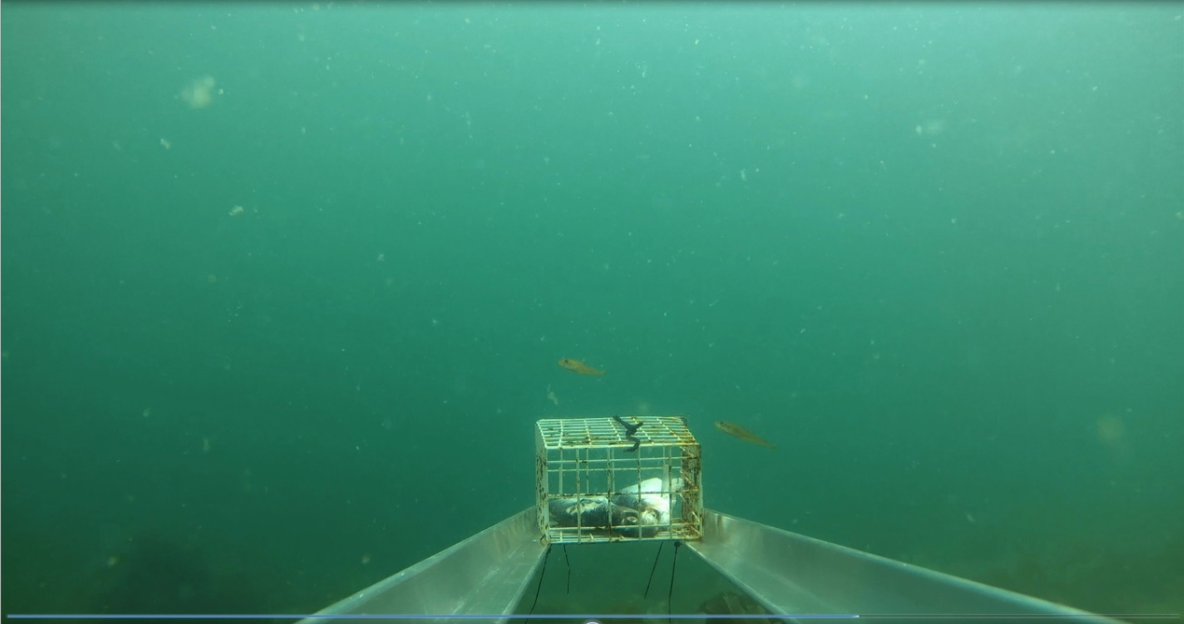

One of a set of identical baited cameras used by NOAA researchers this summer in Kodiak, Alaska.The lightweight aluminum frames and autonomous cameras allow researchers to deploy multiple cameras at once before retrieval.

This summer researchers at Kodiak saw the first signs of potential recovery with beach seine catches of tiny first year cod that are born offshore and drift as larvae into coastal grassy areas in July and August.

“A lot can happen in that first year of life that we would like to learn more about to predict whether or not these year classes are actually going to survive,” said Ben Laurel, a fisheries research biologist with the AFSC based in Newport, Ore., whose specialty is early survival of cold water commercial fish species.

Laurel’s team, which includes scientists from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, has been studying the early life history of Pacific cod in waters around Kodiak every year since 2005. They documented changes in what he calls “young of the year” fish throughout the warm water event through 2016. Right afterwards, they saw no first-year cod but Laurel said things might be taking a turn for the better.

“In 2017 the ocean temperatures started to get back to normal and we did see signs of some fish, which is good because we hadn’t seen fish earlier,” he said. “In 2018 we also are seeing some young fish. But again, we’re just looking at one year in one area and it might not be reflective throughout the Gulf, so we are not sure what it means.”

Ben Laurel, anAlaska Fisheries Science Center fisheries research biologist.

Laurel is taking the tiny cod back to the Oregon wet lab where they will run tests on survival conditions.

“Do they have the likelihood of making it to adulthood just like those fish before the warm water blob? We just don’t know,” he explained. “We don’t have much data on cod during the winter and we can fill that gap in the lab. We can run them through a simulated over winter experience at different temperatures and see what the consequences are of them being a certain size or having certain food available, or what sort of conditions do they need to survive a whole overwintering experience."

The cod study this summer also is expanding to more nearshore areas of Kodiak, along the Alaska Peninsula and the eastern gulf. Laurel credited the AFSC with “really responsive reactions to this drastic reduction in the population,” and adding “more eyes and effort” to understand what happened to the cod stocks.

The research, he said, will provide a window into what might be expected with a changing climate.

“It is kind of a dress rehearsal for what is to come,” he said. “We can’t expect things to stay as they are, and we need to understand these processes and be proactive. I’m encouraged but also nervous about what’s in line for the future. Everybody should be braced for uncertainty.”