Oregon Indian tribes this week declared they oppose two draft wind energy areas off the state’s coast, over their concerns about how fisheries and cultural resources could be affected.

In a statement the Tribal Council of the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians said it recently passed a unanimous resolution expressing the opposition, meeting a deadline for comments to the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

After meetings with BOEM Director Elizabeth Klein, “it was apparent to the Tribe that its concerns regarding offshore wind development’s impacts to fisheries and cultural resources were not going to be addressed in a meaningful way,” Tribal Council Chair Brad Kneaper said in a statement Nov. 8. “We recognize that all energy development has impacts and BOEM has failed to provide assurance that wind energy development will do good and not harm the Tribe, its members, and the greater coastal community.”

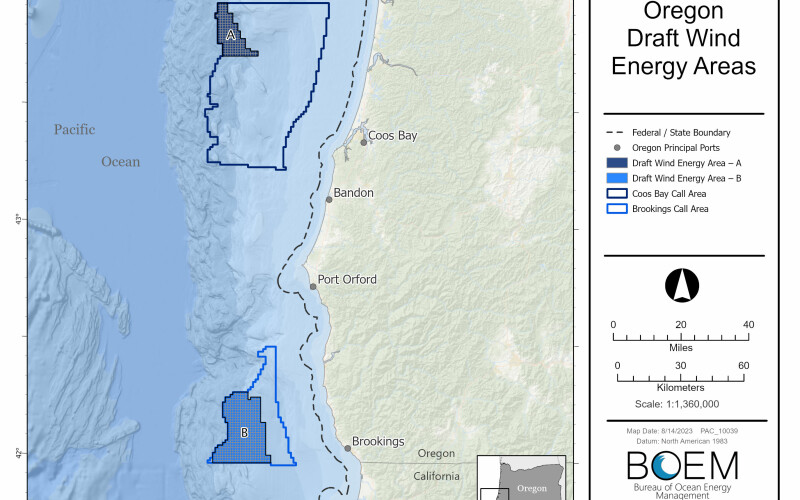

The council said its comments to BOEM have included requests that wind energy areas be at least 12 nautical miles off the continental shelf “to preserve “important, cultural viewsheds” and “avoid areas critical to resident and migratory species, including important areas for fishing.”

“Fishing is an important industry on the Coast that employs tribal members and supports tribal businesses. Fish, including salmon, are also an important cultural and subsistence resource to the Tribe. Any impact to fish from wind development is going to harm our local jobs and the Tribe,” said Kneaper.

“Standards for green infrastructure should not be less than other energy development,” said Vice Chair Doug Barret. “Green infrastructure must not trump the federal government’s obligations to protect tribal resources. That is simply green colonialism, said Doug Barret, the Tribal vice chair. “Because an energy is renewable is not justification enough to rush a process, to ignore or minimize adverse impacts to our community, environment, or cultural resources.”

“The unique landscape, places of religious significance, viewsheds and traditional resources of our Ocean, bays, upland dunes, forests, archaeological features, cultural resources, and first foods connect us to our tribal ancestors,” Barret said in summarizing potential visual effects.

“Our homelands and Ocean have been the foundation of our way of life since time immemorial and remains a cornerstone of our Tribe to this day. As a confederation of coastal tribes deeply dependent on the Ocean and its rich resources, we assert a direct interest in the viewshed extending from our shores, encompassing a distance of at least twelve nautical miles beyond the continental shelf. We believe it is our inherent right to have the ability to see across our viewsheds, as this direct connection is integral to our cultural practices and traditional way of life.”

The Tribe’s Oct. 31 formal comments to BOEM called for a halt to the WEA planning process to allow more study of potential impacts, including effects on West Coast fisheries.

It’s another in a series of pushbacks from Oregon officials, including Gov. Tina Kotek, who in a June 9 letter to BOEM director Klein asked for more time to “allow the State of Oregon to develop a more coordinated approach with the federal government to provide a deeper appreciation of community interests, to engage in meaningful Tribal consultation, and to develop opportunities to avoid and mitigate potential conflicts.”

Other opposing resolutions have come from local governments including Lane County and Coos County, and regional and national tribal organizations, including the National Congress of American Indians.