With boats in fisheries like New England lobster and Bristol Bay salmon getting progressively wider, and fuel getting more expensive, some boat designers believe it’s only a matter of time before fishermen embrace multi-hull vessels. While the ferry and wind farm industries have been taking advantage of the speed, stability, and fuel efficiency of catamarans for years, multihulls have been a hard sell with commercial fishermen.

“You know how it is with fishermen,” says Marathon, Florida boat designer Walter Schurtenberger. “They stick with what they know.”

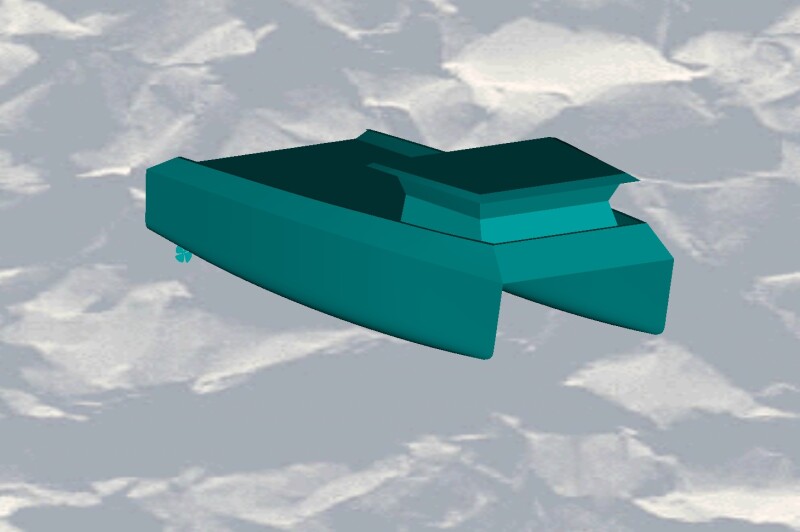

Schurtenberger has designed a 65-foot catamaran for the spiny lobster fishery but has not had anyone build it — yet.

“I had two brothers from up the Keys who were very interested,” he says, but he thinks they dissolved their partnership and neither could fund the project on his own.

“It’s 24 feet wide and has an open stern,” says Schurtenberger. “That way they can back it up to the dock and load traps on pallets with a forklift.”

Schurtenberger estimates that his design, using two 385-hp engines, could cruise at over 20 knots. “Fuel savings with a catamaran would be around 50 percent with a light boat,” he says. “That’s empty. Of course, if you have 600 traps on board, you’re not going to get that.”

Nonetheless, fuel savings are a key motivator for many marine sectors to move toward multi-hull vessels. In Maine, the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries (MCCF) has been partnering for a decade with the Maine Maritime Academy and other organizations on the development of a “green lobster boat,” a tri-hull lobster boat that would be more efficient than the wide, often overpowered lobster boats that dominate the New England and Canadian Maritime lobster fisheries.

“The initial design is for a 38-footer,” says Tom Duym of the MCCF. “They built a 22-foot version that they’re going to test.” According to Duym, Maine lobstermen who have looked at the boat have been skeptical about its stability.

“They’re wondering how it will handle in a cross sea or on the stern quarter,” says Duym. “They think it won’t handle so good.”

Professor Doug Reed at the Maine Maritime Academy has been modeling the design and extrapolating how the boat will handle at its full size.

“The model has a 37.5 horsepower Nana engine, a marinized Kubota. If I can get 12 knots with the model, I’ll be very happy,” says Reed. “That will scale up to 14-16 knots for the full-sized boat. A survey that MCCF did, found that that’s how fast most lobstermen really want to go.”

Reed notes that the covid pandemic took its toll on the project, but he hopes to launch the 22-foot model by summer’s end. “I think it will generate more interest once it’s in the water,” he says.

So far, no catamarans have been reported built for commercial fishermen in the U.S. and Canada. But Northern Ireland boatbuilder Gerry Smyth has designed the Maxus Cat—an 11.95 meter (39.2-foot) long, 5.5 meter (18-foot) wide catamaran trawler that is catching on. Since the launch of the first MaxusCat, the Dignity in 2019, Smyth has built a total of 13 cats, including a 46-foot version, the Lily James launched in 2021. “They’re using them as trawlers, lobster boats, longliners, everything,” says Smyth.

Working with naval architect Ian MacCleod, Smyth transformed his initial idea into CAD drawings and then built a wooden plug. “We took the molds off that,” he says.

“Mostly we use the Cummins QSL9 diesel, it’s around 290 horsepower. Flat out she goes 11 knots at 1,800 rpm. At 1300 rpm they cruise at 8.5-knots,” says Smyth. “It’s not a high revving engine.” According to Smyth, together the engines burn roughly 10 gallons an hour.

“I don’t know how much more efficient they are,” he says of his catamarans. “But they’re an incredible work platform, and there’s the safety of the two engines.”

Schurtenberger agrees on the stability issue.

“The catamaran is incredible stable,” he says. Countering the Maine lobstermen’s skepticism, Schurtenberger believes that his catamaran would hardly notice a cross sea. “Sure it would lift one hull a little bit, and then the other,” he says. “But I don’t see a problem. If you’re heading into a sea, you might feel the waves between the hulls, but it would have to be substantial before it made a difference.”

Smyth reports that he recently made a visit to the Canadian Maritimes, where several boatyards have expressed an interest in building the Maxus Cat. It’s possible that multihull may be showing up in North America in the not too distant future.