National Fisherman Viewpoints- The following op-ed article presents the personal viewpoints of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of the publication, its editors, or its affiliated organizations. The author's perspectives are presented here as a means of fostering open dialogue and diverse discourse on the topic at hand. The publication does not endorse or take responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or implications of the content within this article. Readers are encouraged to critically engage with the ideas presented and to form their own informed opinions based on a range of sources and perspectives.

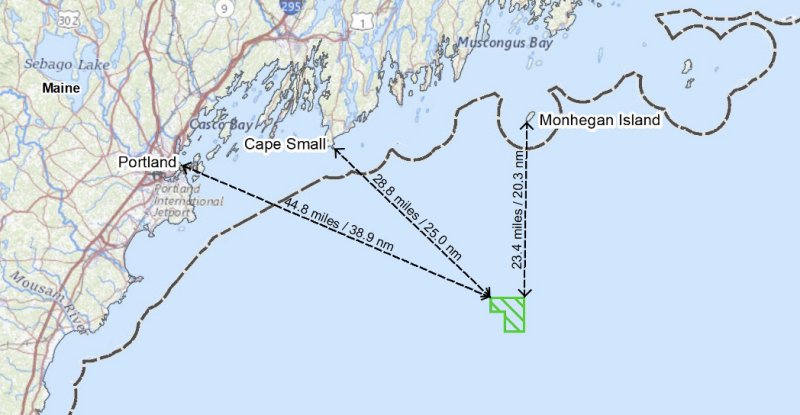

The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management published an announcement in the July 21 Federal Register, advising the public that a “draft Environmental Assessment for the potential influence of an offshore wind research lease in the Gulf of Maine” is now available for comment.

The sharing of ocean space has long been an issue, and the prospect of floating wind farms proposed for 20 miles southeast of Portland, Maine, is bound to raise concerns. Back in 2007, Porter Hoagland of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute – an oceanographer with a focus on economics and ocean resources – wrote:

“The siting of renewable energy facilities does not involve an exclusive use of ocean space in all cases… In making decisions about compatibility and exclusivity, it is critical to quantify tradeoffs in economic terms, where feasible. Importantly, the economic concept of ‘resource rent,’ representing the value of ocean space as a scarce resource, should be utilized in analyzing such tradeoffs.”

Little has changed. In its policy papers Woods Hole has consistently endorsed the idea that where feasible, economic returns should be the priority consideration in allocating ocean space. “I think that’s how any resource economist would look at it,” says Woods Hole researcher Hauke Kite Powell.

“Economic return is an important consideration – but not the only one – in decisions about the use of any public resource,” says Powell. “The time frame for consideration should be long-term to encourage sustainable use and avoid short-term profit taking, such as overfishing. And when you consider other values, like aesthetic value, and cultural values, things can get messy.”

How wind power will compare with fishing over the estimated roughly 30-year lifespan of a turbine installation is not a simple calculation. According to Kite-Powell, the comparative analysis would include data on fishing returns from the affected area, assuming those would remain steady over the 30-year time period, and possible mitigation strategies to reduce losses. Regarding the farms, “We’re looking at the power generated by the farm and the reduction in carbon emissions,” says Kite-Powell. “Economic returns would, by definition, have to be projected.”

With the Biden administration pursuing a goal of permitting 30 gigawatts of offshore wind energy capacity by 2030 and 15 GW of floating offshore wind capacity by 2035, fishermen face the prospect of increasing conflicts with wind farms.