In studies that look at their global impact, fisheries subsidies that nations pay out to build up their capacity to catch fish are defined as “subsidies that encourage fishing capacity to develop to a point where resource exploitation exceeds the maximum sustainable yield (MSY), effectively resulting in the overexploitation of natural capital assets.”

They have long been identified as contributors to overfishing, overcapitalization, and illegal fishing.

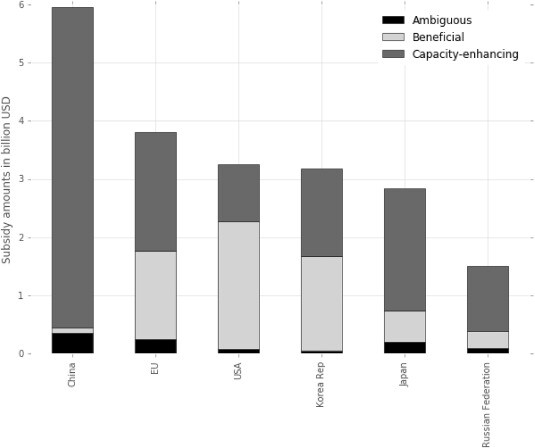

China has spent billions on this type of subsidy – over $5 billion of the $35.5 billion in U.S. dollars spent on subsidies worldwide. The U.S. is also a major contributor to fisheries subsidies, but they are primarily beneficial – not capacity enhancing – subsidies, defined as “investments in the promotion of fishery resource conservation and management.” The US and Canada are unique in spending more on beneficial subsidies than capacity-enhancing subsidies.

But on June 17 the World Trade Organization (WTO) took a step toward leveling the playing field, introducing new rules intended to put a check on fisheries subsidies.

According to Ambassador Santiago Wills from Colombia, chairman of WTO’s Negotiating Group on Rules, and author of the draft agreement, the new rules seek to eliminate or limit subsidies to fishing operation engaged in illegal, underreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

“Article 3.1 contains the basic prohibition in respect of subsidies to IUU fishing, by stating that subsidies to a vessel or operator engaged in IUU fishing or fishing related activities in support of IUU fishing are prohibited,” writes Wills.

Articles 4 and 5 of the new rules curtail subsidies to fishing operations targeting overfished stocks, and or contributing to overcapitalization, respectively.

“Article 4.1 is the prohibition for subsidies for fishing or fishing related activities regarding an overfished stock,” says Wills. “Article 5 contains the disciplines on subsidies contributing to overcapacity and overfishing,” he adds.

“[The agreement] is a great contribution to Ocean sustainability, fisheries, and the livelihoods of millions of people,” Wills tweeted, upon conclusion of the negotiations on the 17th.

But crafting an agreement that over 160 countries can sign on to opens the door to slippery language. The rules would be enforced by the WTO, for example, based on each country’s self-reporting.

Conservation groups are divided on their appraisals of the new rules, with the Pew Charitable Trusts calling them a move in the right direction, and Oceana’s Andrew Sharpless lamenting the WTO’s work.

“After 20 years of delay, the WTO failed again to eliminate subsidized overfishing, and in turn, is allowing countries to pillage the world’s oceans,” he said.