We asked the experts to name their must-haves

In every fishery and on every boat, captains have some electronics that are their go-to for making a safe and profitable trip. Owen Smith had a close call with his 80-foot scallop boat Relentless late this past summer. He managed to keep his electronics safe, including his favorites.

Heading out for an 11-day trip on Aug. 29, a saltwater intake line broke and quickly flooded the engine room. Luckily he was only four miles out from Barnegat Light, N.J., and managed to get the boat back to his dock, where he beached her with no major losses.

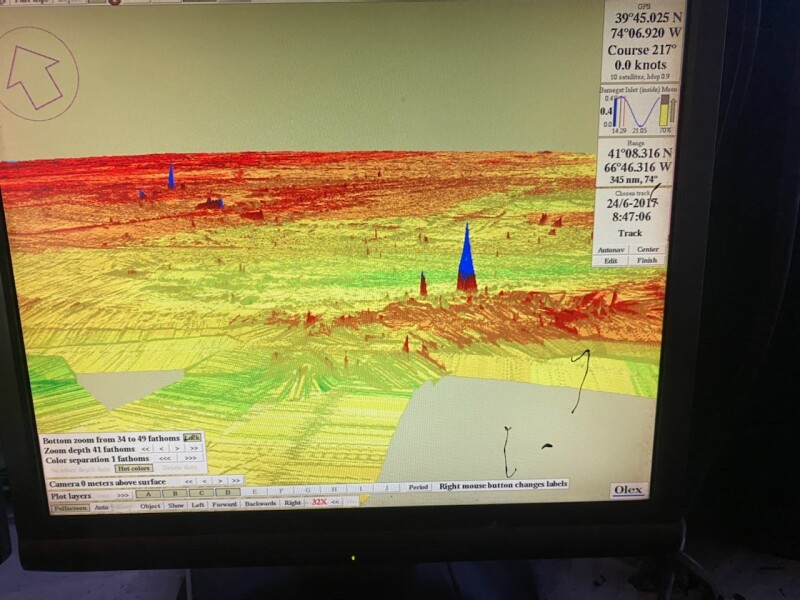

“I have two Olex bottom builders,” says Smith. “Down here it doesn’t matter so much. But in New England, where you have rocky bottom, up in the Nantucket area you’ve got sand dunes, and up in the channel you’ve got all that crazy stuff on the bottom, the Olex creates a visual picture. And you can actually roll it three-dimensionally, so it’s like you’re going through these canyons.”

The Olex bottom builder is something Smith doesn’t like to be without, and that’s why he has two. He has one connected to a Furuno GPS, the other to a Northstar GPS. “One is 12-volt, the other is 24-volt,” Smith says. “We’re doing the redundancy thing, so if we lose one, we still have the other.”

Smith also likes to have two systems because he has noticed that position coordinates of wrecks and other hangs can vary, depending on the GPS.

“There’s something about their internal calculations,” he says. “If somebody gives you numbers for a wreck and they’re using a Furuno system, those numbers might be dead on if you have a Furuno system, too. But if you’re using the Northstar set-up, you might be off as much as a quarter mile.”

Smith keeps both Olex systems running all the time, reading soundings from a Furuno 293 sounder and another transducer that is connected to his Furuno Navnet 3.

“We really like them, when you find a little hole or a neat looking little groove you can say, oh they’re hiding there. I remember a couple of times in that Nantucket area, you can sneak in and find places where there’s a lot of scallops.”

Smith actually picked up on the bottom mapping idea from a 2002 NF article, when the Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, scallopers were pioneering the technology. Almost 20 years later, few scallop boats are without a bottom building system.

For Ronald Dufrene, who fishes his 103-foot shrimp boat Mister Jug out of Lafitte, La., the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico offers little in the way of topography, but plenty of obstacles in the form of wrecks and decommissioned oil rigs turned into reefs.

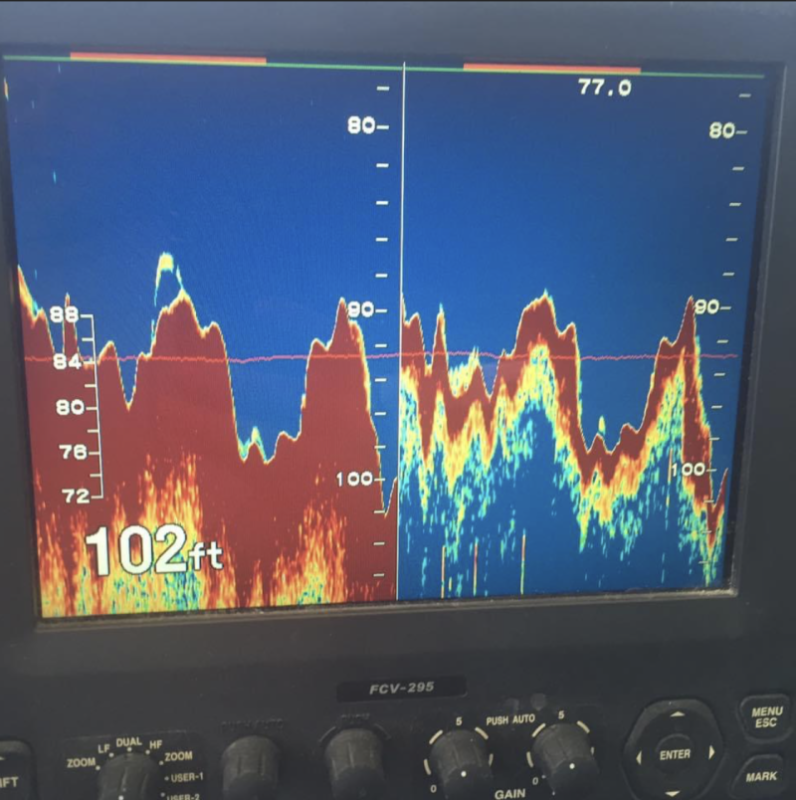

“We like our Furuno split-beam color sounder,” Dufrene says of his Furuno FCV 295 sounder. “It’s got 200 and 50 kc. We have P-Sea WindPlot for navigation, two Furuno radars. I got a Lowrance side-scan sonar. It’s actually made for a bass boat. I’d like to get a bigger one. StructureScan, it’s called. It shows a lot of stuff on the bottom.” Dufrene makes two-week trips that take him, and his crew of three or four, all over the gulf, and he has a satellite phone and satellite TV. “Can’t do without that Direct TV when we’re gone from home so long,” he says.

Dufrene, whose little community was swamped by Hurricane Ida in early September, helped his father build the Mister Jug in 1980 and has fished the boat since then. He knows the bottom and could probably fish blind.

“After 42 years, you could point at a spot on the map, and I could tell you the depth of the water,” he says.

The two devices Dufrene really counts on are his P-Sea WindPlot for keeping him off the wrecks and rigs to reefs, and his split beam sounder.

“The sounder actually sees activity on bottom,” he says. “If we see some activity, we’ll slow down and make a little sample try with a small net.” Dufrene catches mostly white shrimp and brown shrimp, landing anywhere from 40,000 to 60,000 pounds per trip.

Since 2015, Dufrene has been required to have AIS on his vessel and he is not too happy about it.

“It cost me a lot of money to figure out how to fish this bottom without tearing up our equipment. Now, other people can follow our track and just go right back on it.”

While Gulf of Mexico hurricanes pile a lot of bad weather into a single punch, in the Bering Sea the challenges are amplified by foul weather so frequent people just have to get used to fishing in it. TJ Durnan runs the Alaska Spirit for O’Hara Corp., and his wheelhouse has a suite of electronics that would rival a NASA rocket.

“It will look like that when it’s done,” says Durnan. “You know the history of the Alaska Spirit, right?” The O’Hara Corp. bought the 230-foot, 47-year old dragger in 2017 and has been upgrading the vessel every year.

“The wheelhouse is next,” says Durnan. “But right now she’s still that 1960s style, and everything is sort of patched together.” While the configuration awaits a modern wheelhouse, Durnan has all the electronics he needs to find fish and avoid bycatch.

“It’s a pretty standard trawl complement, really,” says Durnan. “The heart of it, obviously, is the fish finders. Our primary sounder is a Simrad ES80, that’s a split beam. It’ll do a biomass calculation for you, but for most of what we fish for, which is sole, they are not very sounder friendly.” According to Durnan, the flatfish that he mostly targets lack swim bladders and are close to bottom.

“Even at 1.28 milliseconds, you still have like a 4-inch dead zone, so two fish or even three can mark as one fish. So what you see as a 42-centimeter fish could be two 30-centimeter fish overlapping. It’s really most accurate when we are targeting Pacific ocean perch, or Atka mackerel. But I rely on that one more than any other.” Durnan’s ES80 can send pulses between 200 and 50 kHz, or lower, and he monitors each frequency on its own screen.

“Our highest frequency on the Spirit is 120 kHz, and then 38 kHz on the low end,” says Durnan. “We also have two Furuno FCV 1200s. I know the frequency on one is 50kHz. In total I have four screens I’m looking at,” says Durnan. “The two for the Simrad, and each of the Furuno’s has its own display.”

While he has pretty much gotten skilled in analyzing what he’s seeing, Durnan admits he has gotten fooled.

“The big boner in the Bering Sea is getting a big bag of Pacific ocean perch instead of pollock, because that comes off the directed fishery quota. I was thinking, who can’t tell the difference between pollock and POP, but then I went out and did the same damn thing, because they’ll present almost the same as pollock. But you know, for the most part, we have a good idea what we’re looking at.”

A few other machines vital for catching fish and reducing bycatch are the Alaska Spirit’s net monitoring and bottom building systems. On the net monitoring, Durnan has been working with a California company called, SmartCatch, which makes a video monitoring system that can help reduce bycatch.

“We were the first to implement that in Alaska, on the Constellation,” says, Durnan, who ran O’Hara’s Constellation prior to taking over the Alaska Spirit. “I brought all that equipment with me to the Alaska Spirit. It’s amazing what the video will show you compared to the acoustic net monitor. That’s the big promising thing down the road for bycatch reduction.”

In addition, Durnan works some hard-bottom areas in the Gulf of Alaska and the Aleutians, and uses a couple of bottom building programs.

“Our main system is the ECC Globe System,” says Durnan. ECC, the Electric Chart Company, sells bathymetric charts and the Globe terrain building systems. In addition, Durnan has an Olex bottom building system for backup.

On the crew comfort side, the Alaska Spirit has satellite internet that its 50-person crew can access at various times of day.

“We turn it on for a couple of hours on either side of the shift changes, so they can check email and Facebook,” says Durnan. “You can’t keep crew without it.” Durnan has gotten used to it, too. “Gone are the days of trying to find the BBC on the sideband to see if there’s still a world out there.”

There is still a world, and captains all around the U.S. coasts are using their preferred tools to catch the fish that feed it.