Originally featured in May 1980 National Fisherman, written by John Gardner.

We have not heard as much of the revival of interest in classic watercraft in the deep South as has been forthcoming from other parts of the country, notably the West Coast. Nonetheless, the South’s involvement with traditional small craft is growing, with real progress already being made.

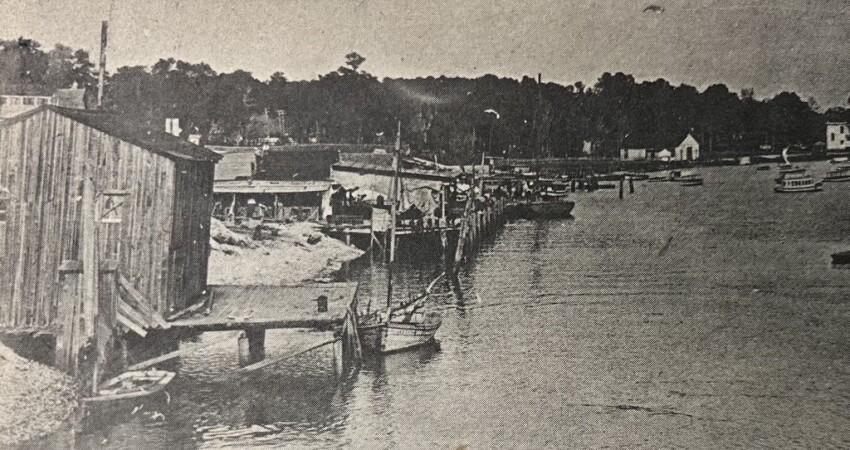

The Coastal Heritage Society of Savannah Ga., now nearly five years old, has been actively at work in Georgia and the lower South Carolina area, and is now undertaking a local watercraft research project, funded in part by a Maritime Preservation grant from the National Trust for Historia Preservation.

The year-long research will focus on the area from Charlestown, S.C., to Jacksonville, Fla., about 300 miles of coast. This project, the first of its kind, will investigate the design, use, and construction of the dugouts, bateaux, and other boats that were and are a way of life along the marshy coastal areas.

Project Coordinator Rusty Fleetwood, who helped found the Coastal Heritage Society in 1975, says that the project is designed to be the first step in the documentation of this region’s small-craft heritage. Although much is known about some of the larger vessels built here, the history of the region’s small craft is little known and has been a neglected aspect of the American experience.

The dugouts, bateaux, and market boats used for fishing and transportation prior to 1950 have, for the most part, disappeared, leaving little trace of their passing. Rusty and his group of researchers are seeking information about such craft ranging in length up to 60’. Photographs are especially desirable. Contact Rusty Fleetwood, Coastal Heritage Society, P.O. Box 782, Savannah, Ga. 31402.

The following paragraphs, from part of a letter received from Rusty a few weeks ago, give some idea of the group’s activities up to now.

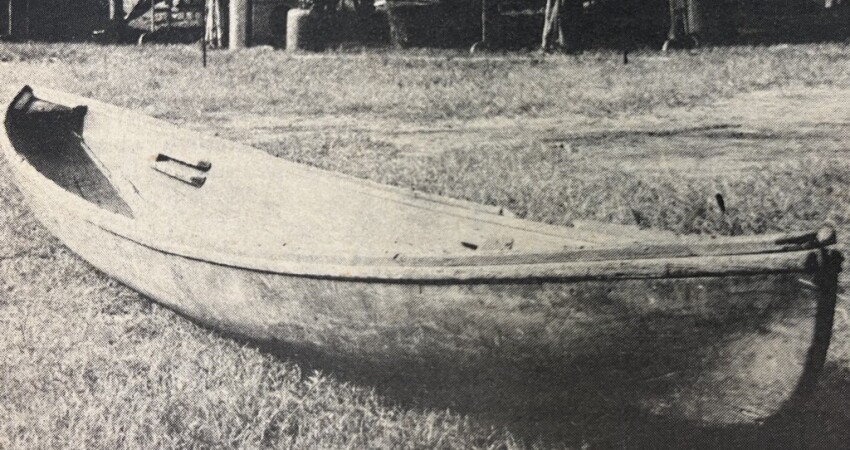

“Three years ago, I got in touch with you, as you may recall, concerning the dugouts or periaguas formerly used on this part of the coast. Since then, I have come up with some interesting facts, even discovering a few folks still alive familiar with the tricks for making sizable cypress dugouts.

As you know, this sort of fact-finding is both slow and exacting. Our organization was about a year old when I first contacted you, has grown considerably. Since our main interest is the preservation of the lifestyles of this area as they were in times past, we determined early on that what was needed was a coordinated research effort into the small craft of former times, considering Georgia and lower South Carolina were tied to the water before the large-scale development of railroads and motor vehicles.

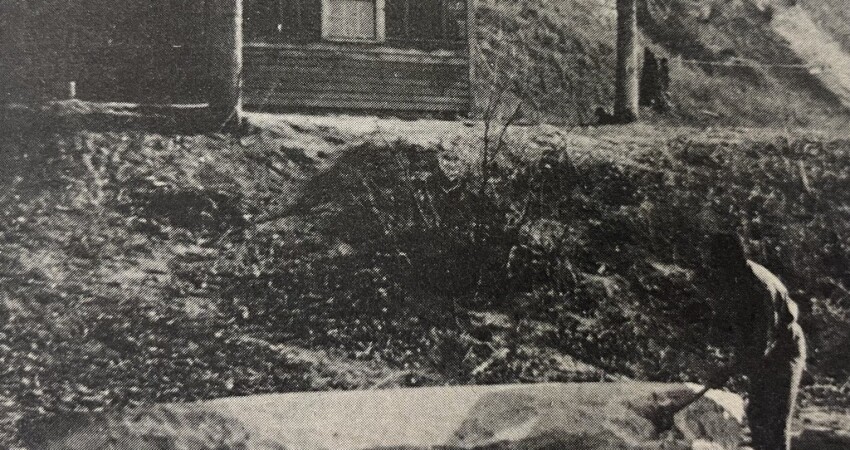

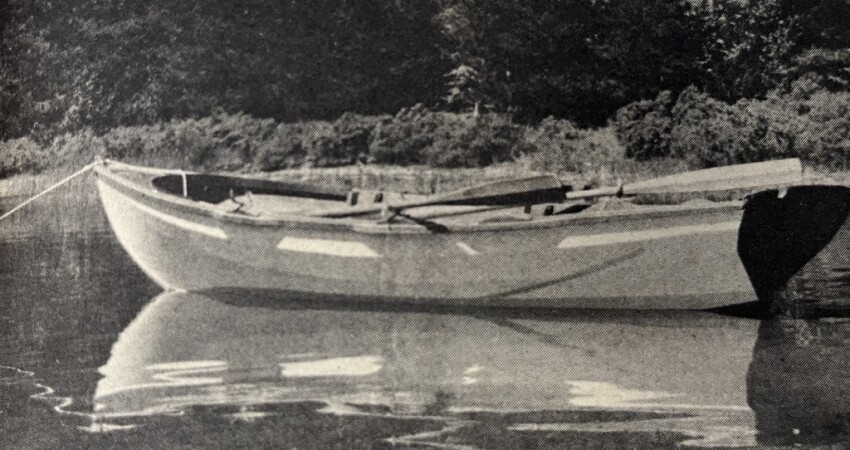

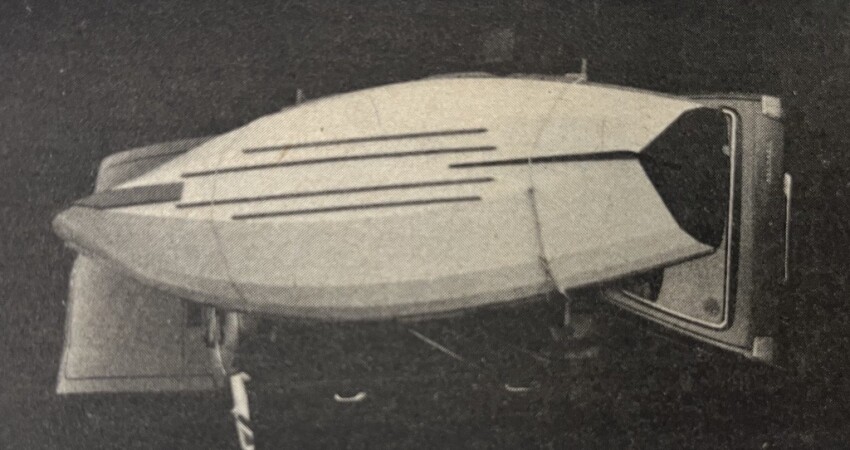

To see to what extent there might be local interest in the region’s bygone watercraft, Roger Gump, a local marine surveyor and boatbuilder, and I constructed as a demonstration, a cypress “oyster” bateau, November at the society’s site on the Savannah River, the design was taken off a hulk dragged from the march, a slimmed-out oyster boat of plain construction, judged to have been built in the 1920s. After completion, the boat was sold to defray costs, and construction of other small craft in the future. However, the main thing was that during the time the boat was building, visitation at Fort Jackson doubled, leading us to believe that the interest in this sort of thing is not limited to boat addicts like ourselves, but is shared by hundreds of other folks in this coastal area.”

More Whitehall Fans

Drawing on information obtained from “Building Classic Small Craft,” Gary Blair of 122 Pleasant St., Santa Cruz, Calif. 95062, has designed a 19’ x 4’ Whitehall for Lee Faraola of Santa Cruz. The method of construction is a novel one, devised by Blair and successfully used for a 14’ Whitehall, also of his design and recently completed. Readers will find this method of interest. The description which follows is excerpted from a letter from Blair.

It will be clinker planked,” he writes, with 6mm (1/4”) Bruynzeel dark African mahogany glued throughout with epoxy. All external edge grain is to be covered with solid wood strips on the lap edges and by a 3/8” hardwood overlay which covers the plank ends at the transom. It will have built-in airtight chambers fore and aft.

I have just finished a 14-footer, posts, deadwood, keelson, etc., are fastened with stainless steel screws and ¼” stainless steel threaded rod bolts (5/16” for the 19-footer). No ribs or lap fastenings. The laps were glued using blocks and clamps at the molds and ½” screws every 2” along the laps between the molds. After the glue hardened, the ½” screws were backed out and the holes bunged. The glue that squeezed out of the laps was easily cleaned off with a putty knife before it cured, as there were no cumbersome clamps in the way. This Bruynzeel plywood is of excellent quality (it should be at $64 wholesale per 4’ x 8’ sheet 1/4” thick). Only about five out of 1500 screws (actually 200 screws were used over and over) stripped in the plywood, and the laps were all pulled up very snug. The garboard/ keelson joint and the plank hood ends, of course, were all stainless steel, screwed under matching bungs.

The weight of the 14-footer when finished was about 180 lbs. You can walk along the planking of the up-turned bottom with the boat supported on horses 12’ apart. There is a little flex, if any, in the skin, and absolutely no hogging of the keel. Floors are 1 ¾” meranti put in with 4” screws through the keelson and outer keel from inside the boat.

It’s not clear how many floors there are and how high up the sides they come. Apparently, they are depended on to strengthen and reinforce the bottom. I have to say that if I were doing this, I should also want a few ribs for additional insurance, even though I had every confidence in the glued laps. These frames need not be heavy or numerous. If they were glued laminated to shape, used instead of solid molds, and left in the boat as permanent members, this could result in some saving of labor.

I have noted a tendency in some of the newer variations of composite plastic/ wood construction to eliminate ribs or frames, presumably to save weight, cut down on labor, and to give an open, unobstructed interior. Doing without ribs also eliminated the need for expensive, hard-to-get bending stock of suitable quality. Several commercial builders are now producing canoes built of glued strips without ribs or frames, and I have not heard of any failures. Nevertheless, I should feel more comfortable if they had a few light ribs just in case. While fully recognizing the dangers and undesirability of over-building, I do want, and insist upon having, a substantial margin of safety.

Blair uses epoxy glue and takes full precautionary measures against its potential health hazards. He wishes a harmless substitute might be found that was equally strong. There are vast numbers of different epoxy formulations featuring different characteristics and requiring various handling and gluing procedures. If one is going to depend on epoxy glue to hold a boat together, he had better make sure he has the right formulation and that he uses it according to specifications. In fact, I would want to do considerable preliminary testing myself in a matter as critical as this.

Glued Boats

Glued construction appears to be the coming thing in California. From 715 Lafayette St., Martinez, Calif. 94553, Howard Benedict sends news and photos of another boat of glued Bruynzeel ply. He writes,

"Enclosed find results of your 'Building Classic Small Craft.' I was taken by the Chamberlain Dory skiff and undertook the construction in April of '78. Spare time had the hull in one piece by July, and not much later in the water, not finished but being sculled about as 'yacht tender' for my 30' Bird Class sloop which we had sailed from San Francisco to Tomales Bay.

During the '78-'79 school year I managed to finish the skiff proper and turned out four 9' Culler oars. Since then, she is hardly ever still, being rowed on Tomales Bay, Carquinez Straits, Santa Cruz and lakes too numerous to mention. Even rowed her in British Columbia.

Once lofted, I set up plywood bulkheads and cut 6mm Okume ply to the plank shapes. At three of the bulkheads, I temporarily fastened three fir 'glue-lam' ribs of 1/8" strips. I used Gougeon's epoxies for fastening and glued the bottom and the planks to the ribs, stem, and transom. Knees, thwarts, and transom are Honduras mahogany, and the rub rail is oak. The exterior of the hull is covered by one layer of glass cloth. The interior seams are double-Blass taped — all wood varnished. As to the strength of the construction, I once dropped the skiff about 2' onto the asphalt paying getting her off the cartop and only scratched the finish.

Thanks to your inspiration, I have received lots of admiring comments. Additionally, my son is building International 14’s of his own design using cedar and similar veneers. His comment on seeing Alerion III in ‘The Small Boat Journal’ was: ‘There’s your boat for Tomales Bay.’ So present plans and thoughts are turned toward cold molding an Alerion III hull. With his expertise, I may just pull it off.”

Power Sanders Overrated

When it comes to their use for wooden boatbuilding, high-speed electric are not as efficient as they are commonly supposed to be. They are costly and are something of a menace. Their high-speed abrasive action throws off clouds of dust which the older cutting tools, such as planes and scrapers, did not produce. Grinding the wood away by reducing it to dust can be less efficient as well as more difficult to control than removing it in the form of shavings. As for expense, there is the initial cost of the machines plus their repair and servicing, the cost of electricity and the sanding disks and belts that hardly come cheap.

The clouds of dust produced are a proven health hazard and are difficult to control in a small boatyard or home shop, even with masks and respirators. Wood dust, with or without residues of paint and plastics, is now recognized as a serious health hazard. Woodworkers exposed to large amounts of wood dust have become permanently sensitized. Recent studies, notably National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health's study of 300,000 death records in the State of Washington, have shown an unusually high death rate from cancer among woodworkers and point to exposure to wood dust as a likely contributing cause.

Scraping and planing does not produce dust, and the old-time boat shop - before the advent of high-speed rotary sanders - was a relatively dust-free place. Sandpaper was used sparingly, yet the quality of the finish on the yachts of bygone days was far superior to what is now produced with power sanders. Planes and scrapers did it.

Hand planes are still with us to a limited extent, but scrapers have all but disappeared from the wooden boat shop. What a pity!

The boatbuilder's scraper is as simple as it is effective. To make one, a small flat of saw steel (old hand saws cut up with tin snips do fine) is filed against the edge on a 45° angle until it is sharp. (An eight or 10" mill file does the job well.) This edge is then turned in a cutting hook with a proper burnisher — that is all there is to it. The scraper can be sharpened and resharpened over and over again, as often as there is a need for it.

There is no shortage of files and scraper blades; though less plentiful, they can still be had. But for all intents and purposes, good burnishers have been all but off the market for some time. The few that have

been offered for sale, while adequate perhaps for cabinet work, are too small and otherwise unsuitable for boatbuilding. which requires a longer, heavier burnisher and one hard enough to stand up under continued hard use.

Fortunately, I can now report that proper boatbuilders' burnishers are again available. The Norwalk Machine Works, P.O. Box 2121, Belden Station, Norwalk, Conn. 06852, has produced a trial run of boatbuilders' burnishers to test current demand. In response to what has appeared in National Fisherman concerning critical shortages of superior boatbuilding tools, I have tried samples in the boat shop at Mystic Seaport and have found them to be excellent. They are available by mail from Norwalk Machine for S10.