A decade ago, iXblue set its sights on building a sonar that fishermen want

About 10 years ago, iXblue — a French tech company headquartered on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea — identified fisheries as a potential market and began asking fishermen what they wanted in a sonar.

“We found that fishermen want two things,” says Christophe Corbières, Fishery sales developer at iXblue. “They want to know the volume of the target shoal, and they want to be able to discriminate species.”

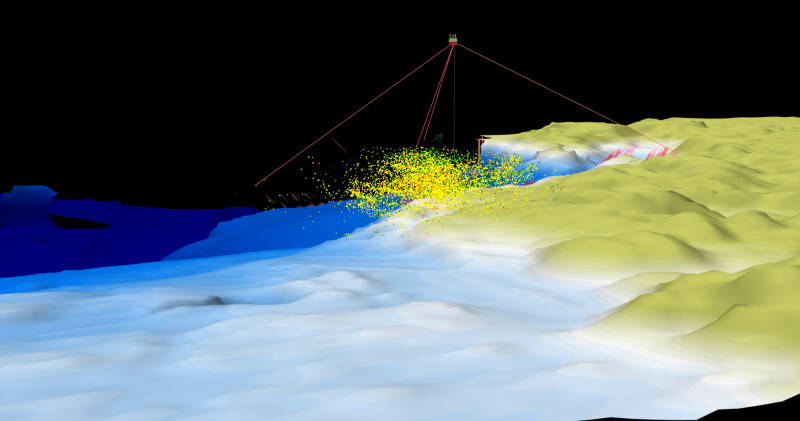

To that end, iXblue designed the Seapix sonar system, a pricey but top of the line tool for fishermen who want to have a good idea what they’re setting their nets on. The system begins with a Mills Cross transducer with 256 beams on each axis.

“It looks ahead and the side 120 degrees,” says Corbières. “We are using the same transducer geometry that astronomers use to listen to deep space, adapted for the sea.” iXblue made the transducer 48 centimeters in diameter, so it could fit the housing size of comparable transducers.

“We made it very compact,” says Corbières. “We also shortened the distance between transducer elements and the analog to digital converter.” According to Corbières, shortening that distance is what helps reduce noise and create a clearer image.

“There are a total of 512 beams,” he says. “If you can imagine a pyramid of signal, at a depth of 100 meters, each side of the base of that pyramid would be 370 meters. That is a tremendous quantity of data that we recover every 5 seconds.” In addition to quantity, Corbières notes that the quality of the data is also a priority. And when it comes to discriminating the size and species of flatfish, that’s a problem Seapix is hoping to solve.

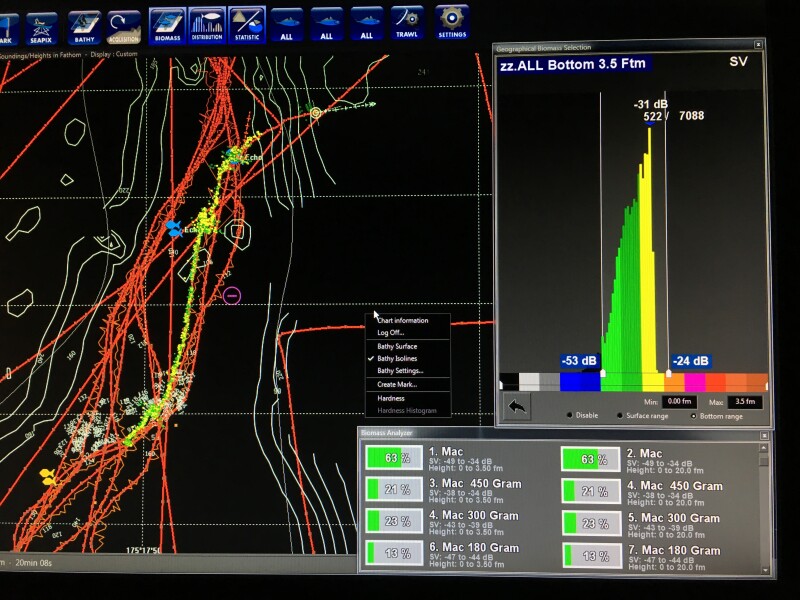

“Right now, there is huge demand for this. Flatfish is complicated. We have vertical resolution of 7 centimeters,” he says, noting that skippers tune the system to their particular fisheries, learn to read the information Seapix provides, and fill in the gaps based on experience.

“In the future, we will divide that resolution in half. We will have 3.5 centimeters of vertical resolution. That will help with flatfish, and our customers are asking for that. In 160 fathoms, Seapix is transmitting at 150 kilohertz.” In order to attain high resolution at depth, Corbières notes, requires 20 times the equivalent energy of a low-frequency sonar. “We are concentrating that energy into very narrow beams that are 1.5 degrees.”

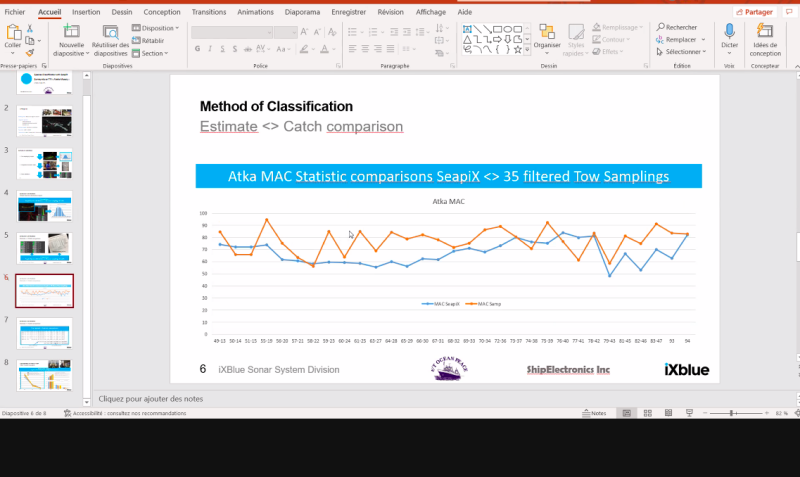

In 2016 and 2018, Corbières spent weeks in the Bering Sea aboard a number of different trawlers, most of which were fishing for Pacific ocean perch, Atka mackerel and cod. These are fisheries that can utilize Seapix capacity to be steered to within 30 degrees of the surface, and where Seapix appears to be paying off, for now.

“I spent three weeks on the Alaska Victory,” he says. “I spent a week on the Evie Grace, out of Kodiak, a week on the Northern Patriot, and four days on the Golden Alaska.” The point to the trips was to ground-truth what Seapix was seeing and what skippers were landing.

“The results were good,” says Corbières. “The true catch was 85 percent of what Seapix predicted for Atka mackerel, 90 percent for cod, and 95 percent for POP.” Corbières notes that they also connected to the Marport net sensors and trawl camera, and saw that some species were better at avoiding the net, which he believes might explain some of the discrepancy between what Seapix saw and what was landed.

Corbières is also selling the system to purse seiners that can use a double or triple transducer installation mounted looking forward and sideways so as to scan from the surface to bottom and 120 degrees from the bow.

Jeff Barnett is one of the skippers of the 225-foot freezer trawler Alaska Victory, owned by Ocean Peace, and he took Corbières out to the Aleutians in 2018.

“There were about five days there where all we could do was jog. We were outside and had no protection.” When the wind died down, though, Barnett and Corbières got to tuning the Seapix system.

“When it comes to round fish, the mackerel and POP, that’s when it really works,” says Barnett. “There’s a lot of times there’ll be a lot of plankton in the water, and it’ll show up like fish. My mate and I will be thinking we’ll have a full bag in an hour, then we bring it aboard and there’s nothing there. It’ll show up like that on the Furuno and the Seapix, but the Seapix has a graph along the side that will tell you if it’s all garbage.”

That’s the key aspect of the Seapix system, according to Barnett. He has a boat to fill with fish, and Seapix helps him make the best use of his time instead of wasting it chasing plankton.

“It’s the same with pollock. We fish pollock sometimes, and the Seapix will tell you what size they are, at least keep you from setting on peewees. Those fish come aboard, you’ve got to take them.”

On his last trip, Barnett found the system wasn’t working.

“I called Chris [Corbières], and we did all the tests and found the system was running on demo mode because the whole transducer was gone.”

Barnett points out that communications technology has changed the service environment.

“I might not even need to go in,” he says. “Sometimes I can contact Chris by Whatsapp and solve the problem. I can show him what I’m seeing, and he can tell me what’s going on.”

Ocean Peace appears to be sold on Seapix, having put it on other boats in its fleet. Barnett notes that the Alaska Victory will be getting the latest version, one that can spot flatfish.

“It’s supposed to be good for flatfish, I’m hoping they’ll show up on it,” he says.

At $100,000 for a single transducer system, plus installation, not everyone is jumping on the Seapix bandwagon.

“As far as I know, we are the only factory trawlers using Seapix,” says Barnett.

The French company is still the new kid on the block, 10 years in.