Two forces are driving the development of digital logbooks: government regulations and fishermen’s empowerment. On Nov. 11, 2021, NOAA begins requiring all federally permitted vessels in the Greater Atlantic Region — North Carolina to the Hague Line — to file trip reports electronically. “The data gets in quicker,” says NOAA’s Allison Ferreira. “It reduces the potential for error.”

Along with NOAA, the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans and the fisheries management agencies of many other countries are also moving toward electronic trip reports, which normally include catch and bycatch statistics. But there is often much more information in a logbook that is of inestimable value to fishermen. Once on a boat I crewed on, the captain’s logbooks were stolen. Someone wanted the map to our fishing grounds, and it was there in those books.

“It’s all about the beast, and the beast is data,” says Lange Solberg, a former skipper of a Bristol Bay salmon boat and now the head of business development North America for Real Time Data, which developed Deckhand, a digital logbook.

While Deckhand is being tested in the Bering Sea opilio crab fishery, Solberg is currently focused on developing the app to meet the needs of fishermen forced to move to electronic trip reports. According to Solberg, Deckhand is being designed to allow fishermen in the Atlantic to feed data to NOAA.

“The issue is the cost of developing the software,” he says. “It’s nearly impossible to customize this for every fishery.”

To resolve that issue, Solberg is rolling out a software customizing engine called Catch Flow.

“Anyone with some programming skill can learn the language, design their own program, and snap it onto our core,” Solberg says. “We had a woman here, and we asked her to try it. She learned it in a week.”

Solberg believes fishermen will be able to do a lot more with electronic logbooks. Real Time Data is based in Australia, where fishermen were faced with Marine Protected Areas without acceptable documentation of their use of those areas.

“When it came time to come to the table, they had no evidence,” says Solberg. “Ninety percent of collecting data is to support management decisions. Fishermen will be able to do a lot more than file trip reports. They will be able to overlay maps on their data and interface with other electronics. Deckhand will redefine what a logbook is.”

For now, Deckhand is available as an iPad app. It can be downloaded for free, but to upgrade will cost. “We’re still working on our price structure,” says Solberg. “But right now it’s $500 a year for the service to connect with NOAA.”

Brett Alger, NOAA’s electronic technologies coordinator, predicts a boom in electronic reporting, and believes fishermen will take advantage of what digital data collection can offer them.

“Right now we have over 10,000 federally permitted vessels in our waters. And of those, 3,000 are using some kind of electronic reporting voluntarily. I think in the next few years, that number will double.” Alger notes that with the Greater Atlantic Region requiring electronic vessel trip reports starting in November 2021, and other regions heading in that direction, electronic vessel trip reports, or eVTRs, will become the norm.

“The Gulf of Mexico and the South Atlantic are going that way, and the Western Pacific is in a rule-making process for pelagic longliners,” says Alger.

Software for vessels mandated or filing eVTRs voluntarily, will come from numerous developers, according to Alger.

To date, NOAA has approved several vendors for the Greater Atlantic region — Safis eTrips Online, Teem Fish Monitoring, and Harbor Light Software.

“I’d imagine there will be more looking to be certified as we lead up to November 2021,” says NOAA’s Ferreira.

According to Alger, some government agencies are also developing software. “The Northeast Science Center has their own software, and some regional offices have their own software,” he says. “There are 42 data elements that NOAA requires. People can choose from various vendors, depending on what they offer,” Alger says. Harbor Light Software for example, offers a 24/7 help desk.

Alger also notes that developers may add other elements used for marketing and traceability, for example, or to empower fishermen.

“We don’t have direct involvement in that other than merging dealer reports with trip reports. Sometimes dealers and fishermen have to make an agreement on data sharing.”

Besides VTRs and dealer reports, NOAA also collects data from observers, electronic monitoring, and vessel monitoring systems. Alger believes software developers will eventually create a single, integrated system.

“Private companies can offer more bells and whistles,” he says. “They can include maps overlaid with catch rates and bathymetric data. Or tools for business development. Fishermen are already doing this, they have had to evolve rapidly in response to covid and market disruption. The Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association is collecting and sharing data among themselves to help manage quota more efficiently.”

Alger believes any system, paper or electronic, can lend itself to errors.

“You can hit the wrong button on an eVTR,” he says. “But the software can catch those errors.”

According to Alger, the switch from paper to digital is going to require a great deal of outreach and education.

“In order for this to work, we are going to have to help people figure out how to log in, find their accounts and enter data,” he says.

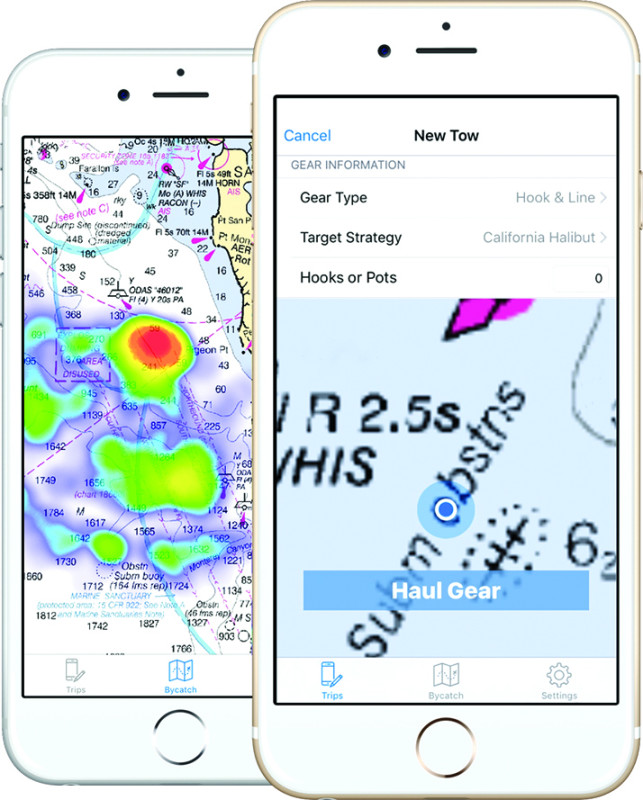

Among those who have developed software, the Nature Conservancy made waves when it purchased 13 groundfish permits in California. The nonprofit organization has transferred those rights to four California communities. But in the process of rebuilding stocks, the NGO developed its own data collection software, eCatch.

“We first developed eCatch to identify bycatch hotspots and allow fishermen to share data,” says Kate Kauer, fisheries strategy lead at the Nature Conservancy. “But of the 10 choke species, only one is still at risk.”

The eCatch logbook was designed specifically for the California Groundfish Collective. Having served its purpose, the NGO has no plans update it. But it was used to monetize data in one way.

“We took the data to Seafood Watch and asked them to do a separate analysis of the collective’s fish,” says Kauer. “Seafood Watch gave the collective’s fish a green light. I love to see the value chain recognize that,” Kauer says, referring to the value of the data.

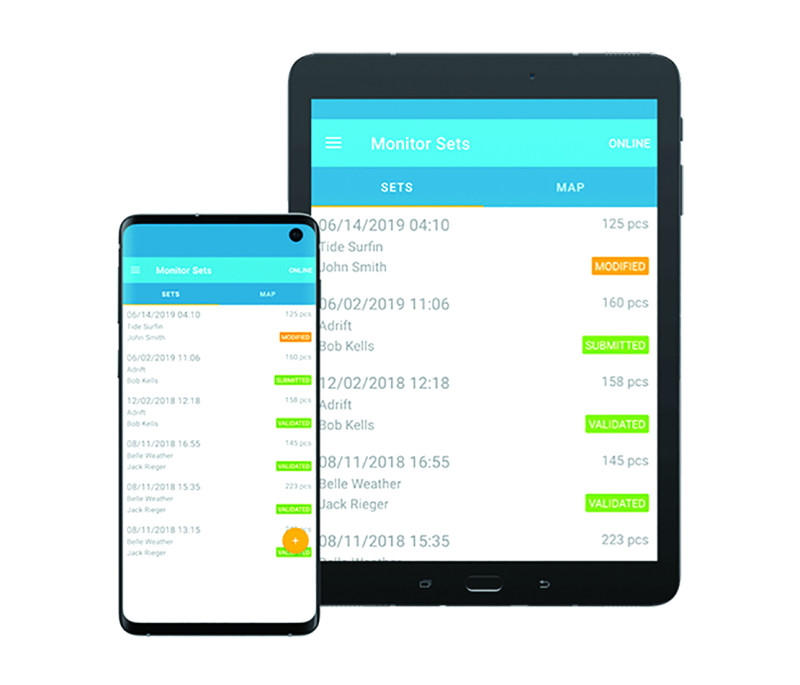

In Canada, Vericatch is the most well-known of eLogbook developers. The company offers eLOG, an app for eVTR submissions to the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

“Just report your catch once, and our system makes sure your data gets to the right people — securely. We pride ourselves on adhering to and exceeding industry standards for data protection and encryption,” says the company’s website. Vericatch’s mobile fisheries app allows fishermen to submit trip reports as well as analyze their own data and shared data.

“The Holy Grail is for fishermen to see where they get their fish, so they don’t have to spend money on diesel searching,” says Vericatch CEO Julian Hawkins. “A digitized logbook is searchable, and you can ask it: Show me where I set, how I set my net, what time of day, and all those bits of information that can help them know where they’re most likely to catch fish.”

Vericatch also makes a program called KnowYour.Fish, which allows fishermen to offer buyers full traceability.

“Some fishermen want to set up a website, put QR codes on their fish and sell them for a better price,” says Hawkins. “They’re giving the story. People aren’t just buying the fish, they’re buying the whole thing.” While most direct marketing is small scale oriented, Hawkins notes that Pacific Seafoods also uses traceability data if they see a benefit. “If tracing adds value, they use it,” Hawkins adds. He believes the value of data and collective data is only beginning to be realized.

“Traditionally, fishermen don’t want to submit their records, they want to avoid it,” he says. But he notes that electronic data is more accurate and more trusted by scientists, and it can lead to better managed and more profitable fisheries.

“This,” Hawkins says, “has value.”