Despite the red king and opilio crab crash in the Bering Sea, pollock trawlers will be allowed to fish in the Red King Crab Savings Area for this season.

The Alaska Bering Sea Crabbers had petitioned the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration last year in hopes of closing the area, after the announcement that the red king crab would remain closed for the second year in a row and that there would be no opilio season for 2023.

The response from NOAA Fisheries to allow continued trawling in the area disappointed leaders in the crab industry, where the economic losses tied to the closed seasons for red king and opilio crab has already been estimated at $287 million by the State of Alaska, and could hit $500 million including peripheral industries.

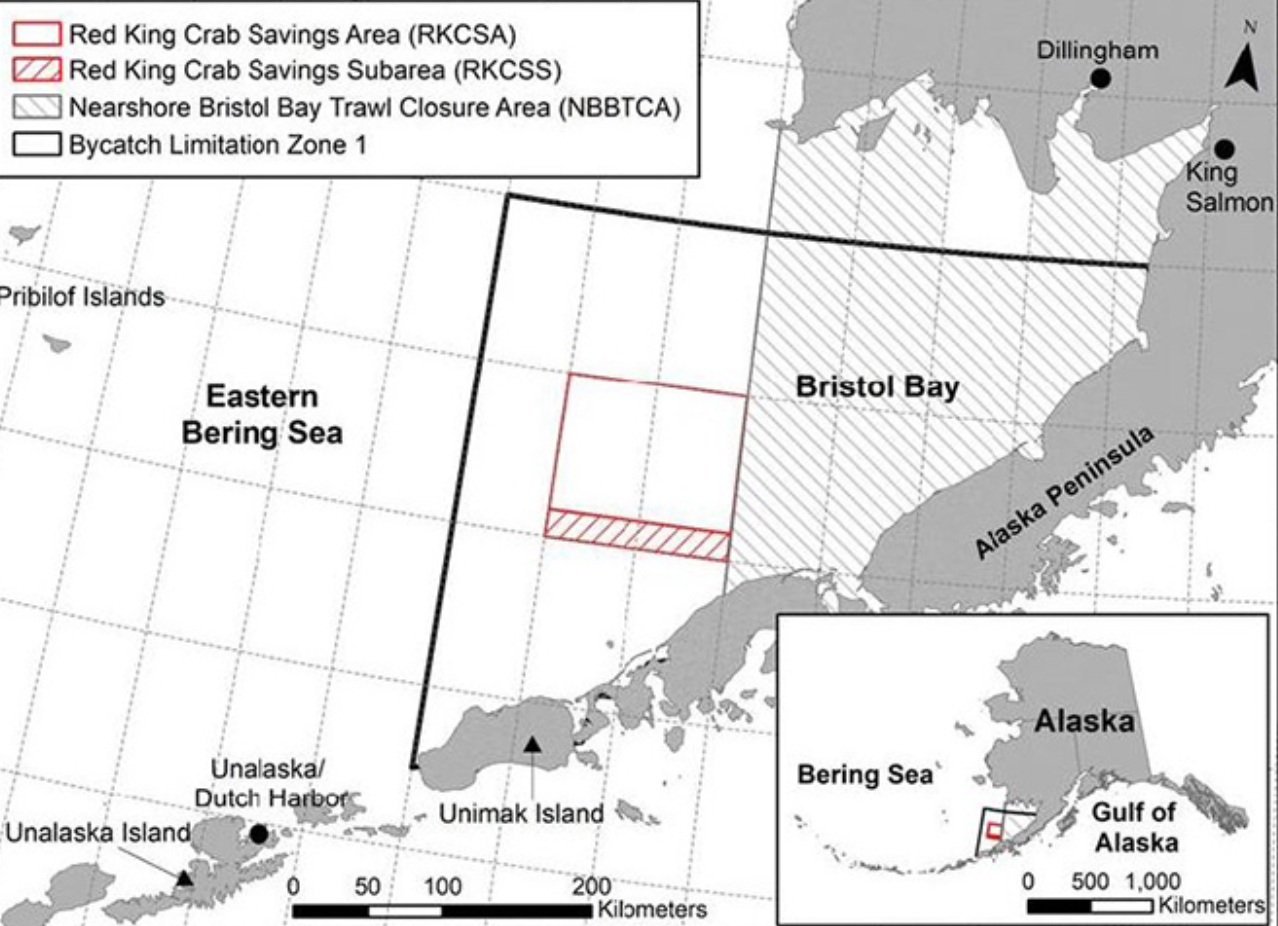

The Red King Crab Savings Area (RKCSA), an area of 3,998 nautical miles (4,600 land miles) in the eastern Bering Sea, has been closed to bottom trawling since 1996; however, mid water trawls and fixed gear, longlines and pots have been allowed to fish inside of the area.

The request was to close the area from Jan. 1 to June 30 to all gear types under emergency regulation as a temporary measure of conservation while a permanent solution would go through the conventional council process of gathering data, public testimony and ruling – a process that can sometimes take years.

“The fishery is collapsed, and we are closed; so this is an emergency situation,” says Jamie Goen, executive director of Alaska Bering Sea Crabbers, in Seattle. “That was the point of the emergency action plan: Let’s put a Band-Aid on it for now and give the stock a chance to recover while we figure out a longer-term plan because the council is going to take at least one to two years, if not more.”

NOAA denied the request on Jan. 20, reasoning that the Bering Sea Crabbers petition did not meet the criteria needed to prove that an emergency exists; moreover that adapting an emergency regulation to close the area did not substantiate circumventing the council process.

“Specifically, the available information does not support a finding that the proposed emergency regulations would address the low abundance and declining trend of mature female Bristol Bay red king crab,” it says in the NOAA announcement.

“We didn’t believe the petition met the ER (emergency regulation) criteria,” says Stephanie Madsen, executive director of the At-Sea Processors Association, in Seattle. “But one never assumes any outcome,” she said of the NOAA ruling.

The North Pacific Fishery Management Council revisited trawl bycatch of crab and salmon during an emotionally charged meeting in December. Testimony during the meeting included evidence that pelagic trawlers operated their gear near the ocean floor from 40 percent to 100 percent of the time when the pollock schools are deep.

As it turns out, however, other gear types targeting halibut and cod in the area account for the majority of red king crab mortality. According to “Considering a Closure to the Red King Crab Savings Area for All Gear Types,” an analytical document prepared in the advent of the NPFMC meeting in December, all gear types fishing the area take varying numbers of animals each year, with the pollock trawl fishery taking but a fraction of the prohibited crab.

From 2013 to October of 2021, all gear types averaged 4,906 red king crabs from January to June, a critical period of breeding and molting in the crab life cycle. In 2015 the incidental take of the king crab hit 15,756. During the same period, pollock trawlers caught an average 8 king crab with a high of 23 animals in 2019.

As for the validity of the data pertaining to the incidental take of crab, Madsen reports that each of the 13 vessels operating inside of the RKCSA rely upon two observers and multiple onboard cameras.

“Clearly, we’re not targeting trawlers,” says Goen. “We need to look at all sectors, including the directed fishery. We’re closed right now, so all of our impacts are gone.” Goen adds that research scheduled for March will hopefully yield information that leads to refinement of crab pots to cut down on the incidental take of females.

A point of contention among crabbers is that for every crab making it back to the cod end of the trawl many more may have been killed by headgear when the nets are towed near the bottom.

“This could have a substantial impact on crab recovery,” adds Goen.

Red king crab abundance surveys last summer revealed 120 mature female king crab per square nautical mile within the RKCSA, and the greatest concentrations of legal male crabs were found in the northwest and southeast corners of the area. Given the tapestry of other habitat protection areas that are closed to trawling, displacing the fishing effort inside of the RKCSA could land gear on areas of greater crab abundance.

Among action steps to mitigate the red king crab decline the council in December initiated efforts toward more studies including the use of crabbers beginning in March as test boats to glean data that could drive management changes by late 2023.

For the crabbers that could be too little, too late, given the speed of the process.

“To be clear, I think we need trawling out there,” says Goen. “We need to be bringing healthy protein to the world. We need food security, but we’ve got to balance it in a way that doesn’t harm other stocks or that helps all of these stocks be as sustainable as possible.

"There's a way to do it; we’re just going to have to work better together, and we’re going to have to move in time and space to be able to harvest and maximize all of our allocations.”