Kelp mariculture is expanding in Alaska and around the world. Kelp farms have been established in Kodiak and Southeast Alaska for a few years, but it’s a brand new industry to Prince William Sound and Kachemak Bay.

The crew at the Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute in Seward has hatched a kelp nursery to support local farmers plant seeds in the sea.

Kelp is extremely versatile and used in a variety of products, including food, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and biofuel, according to the institute’s Science Director Maile Branson.

“Kelp is also highly productive and sequesters large concentrations of carbon, counteracting localized ocean acidification,” she added. “Therefore, in a regenerative ocean farming system, kelp can benefit both the farmer and numerous marine species.”

The Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute is assisting farmers with startup logistics by growing “starts” to establish their ocean-based farms. The institute’s staff is in its second year of kelp production for seven test sites and three commercial farms in the sound and Kachemak Bay.

Alutiiq Pride is a major subsidiary of the Chugach Regional Resources Commission, a tribal consortium representing the natural resource interests of seven tribes in the Prince William Sound and Cook Inlet region, according to Branson. Kelp farming fits nicely into the organization’s commitment of establishing mariculture opportunities with the goal of economic enhancement for residents of the region.

Thea Thomas set up Royal Ocean Kelp Company in the sound near Cordova in 2020 and outplanted her first starts from Alutiiq Pride in October — a winter crop that grows from October to April. Thomas and her partner will harvest their first crop in April or May.

Thomas has been commercial fishing in the area since the 1980s and saw kelp farming as something beneficial during her off-season.

The beauty of kelp mariculture is that it is a winter industry that doesn’t conflict with other uses of the ocean like tourism and most fisheries, while offering employment and use of idle fleets and processing plants in the off-season, according to Jeff Hetrick, Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute’s mariculture director.

Meanwhile, back at the lab

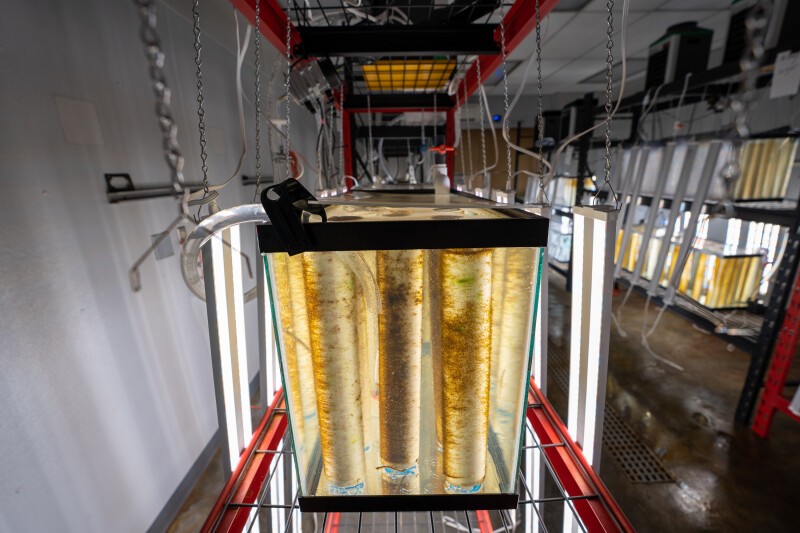

Don’t expect the institute’s kelp nursery to be lined with pots under lights containing little green sprouts.

Instead, you’ll see a series of 2-by-15-inch plastic pipe wrapped with 200 feet of nylon twine and inoculated with kelp spore solution. The string is monitored and controlled with temperature and light until the plants germinate and are ready to be shipped to farmers or test sites at approximately six weeks.

“It takes a lot of time and care to tend to the seed string for a couple months but it is very rewarding to see the kelp grow on the string,” said Michael Mahmood, the institute’s production manager.

Mahmood was able to help plant kelp spools at a farm in Kachemak Bay near Homer this fall.

“It was nice to see things that I grew being planted and being a part of that,” he said.

The seed production process begins in late summer or early fall when adult kelp in the wild releases its reproductive tissue call sorus tissue, Mahmood said.

The trick is to collect the fertile sorus right before the spores are released, whisked to the nursery and treated to trigger spore release, Mahmood explained. Once the spores are released, the fertile solution is used to inoculate spools of line where the spores will settle.

The state requires kelp collected for spore production be within a 50-mile radius of the actual kelp farm.

Alutiiq Pride is working with three species: bull kelp, sugar kelp, and ribbon kelp. Several farm test sites have been established for all three species in collaboration with the Native villages of Chenega and Tatitlek, according to Branson.

Currently, Alutiiq Pride is only permitted by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game to do test sites and cannot sell product, said Mahmood.

Ready for planting

Thomas’ farm was ready with anchors, lines and buoys last fall when Tesia Bobrycki, director of regenerative economy at the Native Conservancy in Cordova, showed up with 14 kelp spools produced at Alutiiq Pride.

Bobrycki helped obtain fertile wild kelp for the institute and deliver the finished product to Thomas’s farm.

The spools are then unraveled onto the grow lines, suspended by buoys approximately 7 feet below the surface, and monitored by the farmer for six to seven months until harvest in the spring.

“The kelp grows very rapidly and will reach lengths up to 10 feet in April when they will be harvested,” Hetrick said. “The test harvest last year yielded about 5 pounds per foot of grow-out line at harvest,” he added.

But the big question is: “Where does it go from there?” asked Thomas.

“This is a brand new industry in PWS, and right now we do not have any established processors or buyers,” she added. “But that’s what we’re working on this winter.”

She has had zoom meetings with several processors in her area that resulted in two possible candidates: Peter Pan Seafoods in Valdez and Camtu’s Alaska Wild Seafoods in Cordova.

“Next spring will be the real telling: What kind of growth we get, what kind of harvest,” Thomas said. “I feel pretty good at the start of it.”

“We’re just very grateful to APMI and Jeff for working with us and providing us the seed twine. It just went so well,” she added. “This is definitely a pilot year.”

Nancy Erickson is a freelance writer living in Moose Pass, Alaska.