O’Hara Corp. launches a 229-foot Bering Sea freezer-trawler after off-season overhaul

Frank O’Hara and the O’Hara Corp. had to buy the Alaska Spirit on faith. He and his team did not get much of a look at the boat before they signed on the dotted line.

“We had to take her as she was, where she was,” says O’Hara. “We weren’t even sure we had a deal for a long time. FCA [Fishing Company of Alaska] was keeping it all secret, and then all of a sudden it went through.”

O’Hara Corp. is a fishing company that began in New England in 1907 and has been carried down through four generations of the family. O’Hara credits the success of the company with having good people onboard, his three sons, and a cadre of trusted experts.

“It’s important to surround yourself with very knowledgeable people,” he says, noting that he really needed them in 2017. Despite more than a century of history and experience, it was a precarious time for the company.

“We were supposed to get the Alaska Spirit and the Alaska Juris,” says O’Hara. “But we only got the one boat, which, in a way, worked out for us because we had the Araho coming around the Panama Canal. And then we purchased the Alaska Spirit, and she needed a more work than we realized as we peeled back that onion. The Alaska Juris wasn’t as well maintained, and if we had had to deal with all that deferred maintenance on that boat, we would have really had our hands full.”

According to O’Hara, the Alaska Spirit was enough, and what they got with her was a great platform in need of a serious upgrade. The 229-foot vessel was originally an offshore supply boat built at Halter Shipyard, in Lockport, La., in 1974. In the late 1980s, FCA took the vessel to Japan and converted it to a head and gut freezer trawler. That created some problems for O’Hara.

“The factory was a Japanese-style factory, the equipment and gensets were all Japanese, everything written in Japanese,” he says. “We had to have a Japanese technician onboard the first six months just to run everything. What we’ve done over the last few years is make it into an American boat.”

That started with replacing the vessel’s archaic net-hauling system, which was basically a mechanized version of hauling twine the way the earliest eastern-rig trawlers did.

“They used the trawl winches to bring the footrope up, and then used the booms to flake the twine aboard,” says O’Hara. “We replaced that with a crane and two jilsons, but that was temporary. The strain when a full bag came down off a sea was too much on the supports for the jilsons.”

During the vessel’s 2021-22 down time, one of the improvements included the installation of two net reels at the forward end of the deck and a new gantry over them.

“We put in two new Rapp winches for the jilsons, and a cod-end transfer winch,” says O’Hara, noting that the cables from these winches run through blocks on the new gantry and can handle the weight of a full cod end being lifted and dropped by big waves.

In addition to the new gantry and net reels, the 2021-22 improvements included all new stainless steel piping, replacing the old galley with new galley equipment, including stainless steel cabinetry, and replacing the hard worn stern structure with a new one. These improvements were the culmination of five years of intensive work to turn a nearly 50-year-old vessel into a state-of-the-art H&G freezer trawler.

“One of the first things we did in 2017 was replace the gensets,” says O’Hara. “We added the new North Pacific crane and new Pullmaster-25 deck winches. We found we needed more power, so we took out the two 400-kW Yanmar gensets and replaced them with two 550-kW Cat C18s.”

After fishing the somewhat improved vessel through 2018, the crew tore out the old factory on the way south in the fall of that year. “In the fall of 2018, winter of 2019 we installed new Carsoe factory. The Japanese-style factory had a big table in the middle, conveyors and plate freezers, but they didn’t have packing stations or scales,” says O’Hara. He points out that the old factory was set up for high volume whereas his people wanted to focus on high quality and better yield. “We wanted to make sure the head cuts gave us the best weight, and we wanted to get the right weight in the pans,” he says. To further guarantee quality, the Alaska Spirit got a new refrigeration plant with two additional plate freezers by supplied by Highland Refrigeration in Seattle.

The 2018-19 refit also included tearing up the old wooden deck and installing double layer of steel. “We also opened the stern void spaces and converted them to a workspace and storage, sand blasted the water tanks, and replaced steel angles inside of the gantry,” says O’Hara.

Elliott Bay Design Group did the design and engineering for the multiyear project.

“We mostly did the steel and stability work,” says Elliott Bay Naval Architect David Turner. While the Alaska Spirit underwent modifications that added a lot of steel above deck — the gantry for the jilsons and the new winches, for example — Turner notes that it did not have much impact on the boat’s stability.

“These older oil supply boats have a lot of stability, more than might be designed into a modern trawler, they also don’t have the tall superstructures you see on new trawlers,” Turner says. “That gives you a lot of margin when you’re working on these boats. The changes that we made did not significantly change the CG [center of gravity] of the boat.” Turner is no stranger to the Alaska Spirit.

“When I started work for Elliott Bay in Louisiana, in 2010, one of my first jobs was to update stability report on the Alaska Spirit. So, you could say I’ve been following this boat.” He notes that the project had its challenges. “Whenever you’re retrofitting structure on an existing vessel, it’s a major change, and it’s an interesting process. The whole gantry foundation work was very precise.” To make it more challenging, Turner points out, there were very few drawings from the 1989 conversion that took place in Japan.

“Not only do we have very few drawings,” he says, “two thirds of them are in Japanese. We had one of our naval architects who was fluent in Japanese, so she used to help us out.”

Turner speaks highly of the O’Hara Corp.’s approach to the project. “I’m impressed with the O’Haras. A lot of the work they’re asking for is not just improving the performance of the vessel, but the safety as well, such as the way the gear gets handled, and their maintenance schedule. They don’t shy away from doing what’s needed.”

Every year since closing the deal for the Alaska Spirit, the O’Hara Corp. has funded improvements with money set aside under the Capital Construction Fund — a long running federal program that allows fishermen to defer taxes on revenues and invest that money into building new vessels or upgrading old ones.

“It requires a minimum expenditure of $100,000 per year,” says O’Hara with a laugh. “We don’t have any trouble reaching that.”

Steel was on the menu for 2019-20 upgrades, with work done at Dakota Creek Industries.

“We replaced some steel at Foss [Maritime] when we got the boat. Later, at DCI we replaced 100 feet by 30 feet of bottom,” says O’Hara. Up above, they added a new deck in the cargo hold and started steel work for new aft winches. In that busy off season, the vessel also got a new aft fiber room, new exhaust stacks with silencers that significantly reduced noise on deck, and steel replaced forward in technical water tank after sand blasting.

“We replaced the winch engine with new 1000-hp C32, and a Marco gear box,” says O’Hara. “They had a Hanshin in there, but again it was all Japanese technology, and hard to get parts for.” Looking to improve crew comfort, O’Hara notes that the vessel also got new heads and showers in the crew accommodations.

“We also replaced the pilothouse windows with larger heated windows” he says.

Things just keep getting better, the following year, 2020-21, the company added new Rapp Hydema hydraulic winches.

“The Araho has electric winches,” says O’Hara. “And if we were building new, we would go with electric, but we don’t have the power on the Spirit. We really can’t do it without a shaft generator, and everything is already set up for hydraulic. We would have had to redo all that.” Along with the winches, improvements included new stern and ramp rollers, replacing a 110-kW electrical hydraulic pump and motor, redoing the hydraulic piping for the winch system, and the installation of a safety and deck gear house.

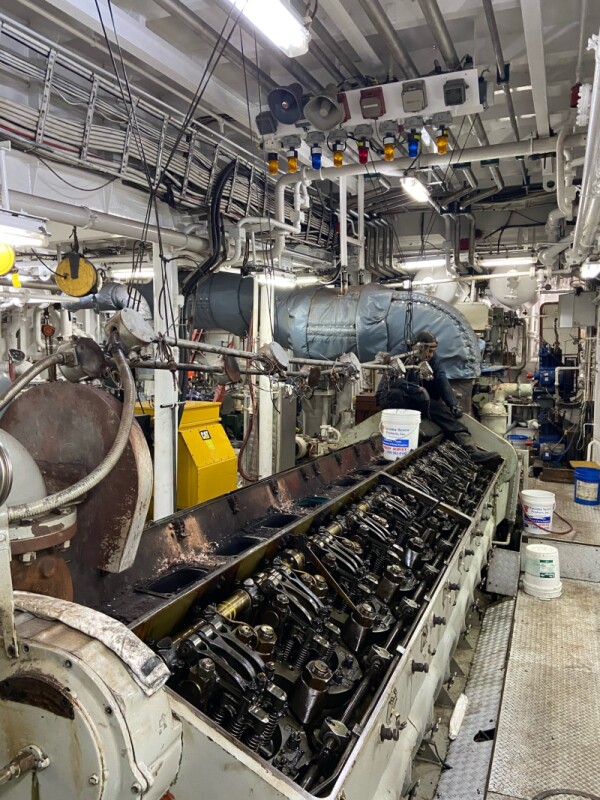

About the only engine left from the original is the 40-plus-year-old 20-cylinder EMD main. According to O’Hara, the utility and longevity of the engine is a factor of its design.

“In most diesel engines, the head covers all the cylinders, or sometimes three, but the EMD has individual power packs that get dropped in and bolted to the crankshaft. So if you have a problem with one, you pull it out and you can drop the new one in in three or four hours.” O’Hara notes that the Alaska Spirit carries spare power packs, which include the cylinder, sleeve, piston, injector, etc., and that the replacement operation can be performed wherever the boat is.

“There is an I-beam above the engine they use to lift the 400-pound power packs out and put in a new one. You take the old one and put it in the box of the new one, roll it out of the way, and send it in to be rebuilt when you get back.” O’Hara notes that regularly replacing the power packs can be part of engine maintenance.

The Alaska Spirit has 50 bunks.

“We carry two observers, and eight to 10 of what I call ‘officers’ — the captain, the mate, engineers, cooks, factory foremen, and deck boss. Then we have around six deckhands and what we call combies, guys who work at processing and work on deck and if there’s no gear work to do, they help with processing. And we have 30 processors.” As noted above, keeping the crew safe and comfortable has been a big part of the conversion.

Only the captain will have to wait for an upgrade. While no major work is scheduled for the 2022-23 off-season, the following year, O’Hara expects to see the wheelhouse modified. “Right now, it’s set up for the way the Japanese fish, which is you have a fishing master and captain. We just have the one, the captain or the mate.” O’Hara notes that the vessel has the latest electronics, including a Simrad ES80 sonar and new transducers. But in two years they will reconstruct the wheelhouse to consolidate the electronics around the helm and add observation wings so that the captain can get a better look out on deck.

In the course of its lifetime, the Alaska Spirit has seen many changes, from an offshore supply boat to a Japanese-style trawler, and now to a modernized head and gut freezer trawler ready for the rigors of the Bering Sea.

Inside the Alaska Spirit

Home port: Seattle

Owner: O’Hara Corp.

Builder: Halter Shipyard in Lockport, La. Rebuilt at Dakota Creek Industries, and other yards

Hull material: Steel

Year built: 1974

Fishery: Amendment 80/Yellowfin Sole

Length: 229 feet

Engine: 3,500-hp, 20-cylinder EMD

Generators: 2 550-kW Cat C18 gensets, 1 746-kW Cat C32

Power train: 12-inch-diameter shaft, 12-diameter, four-blade, controllable-pitch propeller

Fish factory: Carsoe

Refrigeration: Highland Refrigeration

Hold capacity: 600 tons

Crew accommodations: 50

Electronics: A range including Furuno radars, Simrad ES80 sonar and net monitor system

Deck gear: Rapp split winches, a range of Pullmaster winches